And we’re back. Back to Qikiqtaruk – Herschel Island after two weeks away and A LOT of logistics. Have you ever wondered what it takes to plan for a three-month-long field season? In this blog post, we will reveal all of the secrets of Arctic science logistics.

The Twin Otter lands on Qikiqtaruk – Herschel Island. This moment is the culmination of months of Arctic science logistics. Let the science begin! Photo by Alex Beauchemin.

Team Shrub’s summer preparations begin months before we head up North, logistics planning only accelerates once we reach Whitehorse and then it kicks up a notch further once we reach Inuvik. Through out the summer about half of the work we are doing is arguably the logistics of our field research program. In this blog post, we will share with you all of the ins and outs of the logistics behind the science that we do.

Perhaps not the best packed pallet at Aklak Air. This is the first pallet that the new Team Shrub field had packed and it may or may not have been up to Aklak standards, but as the summer logistics progressed, the crew are now expert pallet packers! Photo by Isla Myers-Smith.

This year, our journey to the field started with the whole crew together at the Vancouver International Airport. With some arriving only an hour before departure (due to last minute shipping issues with our equipment – classic!), we scrambled to check over a dozen bags and to get our large collection of lithium batteries through security in time for our flight. In addition to helping replace the used phenocam batteries from both Kluane and Qikiqtaruk, these batteries will be used for several new projects this field season. Read more about our battery-intensive ARU and wildlife camera endeavors in our last blog post.

The Team Shrub 2024 field crew gathers at the Vancouver Airport to head north from the University of British Columbia to the Yukon. Photos by Judith Myers (left) and Isla Myers-Smith (right).

Before Northern and Southern Team Shrub had to part ways for a month, we spent a few days together in Whitehorse and one special day in Kluane. Our Whitehorse days (and nights) were occupied by packing, purchasing more lithium batteries, designing field equipment, and checking out local coffee and book shops to get our last latte fixes and to purchase reading materials for the summer. And our Kluane days were spent getting settled in our southern research site.

The first days of the field season were spent learning plant species and getting settled into our southern Yukon research home – the Outpost Research Station. Photos by Elias Bowman (left) and Isla Myers-Smith (right).

One of our goals this year is to set up “muskox-proof” field equipment to solve our multi-year struggle of keeping our tundra field cameras upright. We’ve been collaborating with Duncan’s LTD, a metal fabrication shop in Whitehorse, to design musk-ox-proof camera and audio recorder stands and are excited to share how these stands fare against the elements and wildlife at this point in the summer, so far so good!

Collecting the new tripods and testing out one of our new muskox-proof “TURTLEs” in the field. Photos by Elias Bowman (left) and Isla Myers-Smith (right).

Once we reached Kluane, we hiked up to the Kluane Plateau, identifying as many plants as we could along the way. The whole team has become heavily invested in iNaturalist, an app that allows users to upload observations of the biodiversity around them. Created by MSc students at the University of California Berkeley, and now funded in part by the National Geographic Society (like us), observations uploaded on the app form a public dataset with millions of records for all kinds of species.

Ciara learning her plant species along the edge of the Alaska Highway at the start of the field season. This summer we have challenged ourselves to ID 500 species across the Yukon, NWT and Northern BC. Photos by Alex Beauchemin (left) and Elias Bowman (right).

We’re looking forward to finding out which member of the team will have the most observations by the end of the summer! (FYI, it will probably be one Cameron D. Eckert.) Our big update is that we just reached our milestone of 500 unique species in the Yukon and Northern BC identified by our team and a whole collective of other iNaturalists out there providing species IDs for our observations and verifying of our IDs!

Ciara snaps a photo of a blond black bear – how confusing – that was later posted to iNaturalist causing a minor iNaturalist debate about what species it was. Photo by Elias Bowman (left). On 28th July 2024 we reached 500 species identifications on iNaturalist during this summer’s fieldwork. What an achievement Team Shrub!

After an adventure-filled five days in the Southern Yukon at the start of the season, it was time for the Team Northern Shrub to tearfully say goodbye to Team Southern Shrub and head off to Inuvik. Despite leaving Kluane seven hours before our flight, we still rushed with last minute gear pick-ups and packaging in Whitehorse. Yet again, we were in for hectic pre-flight logistics that left us repacking bags and weighing equipment a mere half hour before take-off.

One part of Team Shrub Arctic science logistics is that we always have too much stuff. Too much for our car, too much for the plane, just too much in general, but every item has its use in our fieldwork. Photos by Alex Beauchemin (left) and Elias Bowman (right).

This time it was our heavy and awkwardly shaped custom metal tripods that caused faff rather than our batteries. To our dismay, we learned that our tripod legs – ingeniously packaged in a fishing pole tube – exceeded Air North’s 203 cm baggage length limit by a whopping 4 cm! Thankfully, we were eventually told that our pole would indeed be able to fit on the plane and we were on our way in no time.

One of the most stressful stages of Arctic science logistics is flying places with all of our gear. But, thankfully Air North, Yukon’s Airline is very accommodating of Arctic researchers with too much gear! Photos by Elias Bowman.

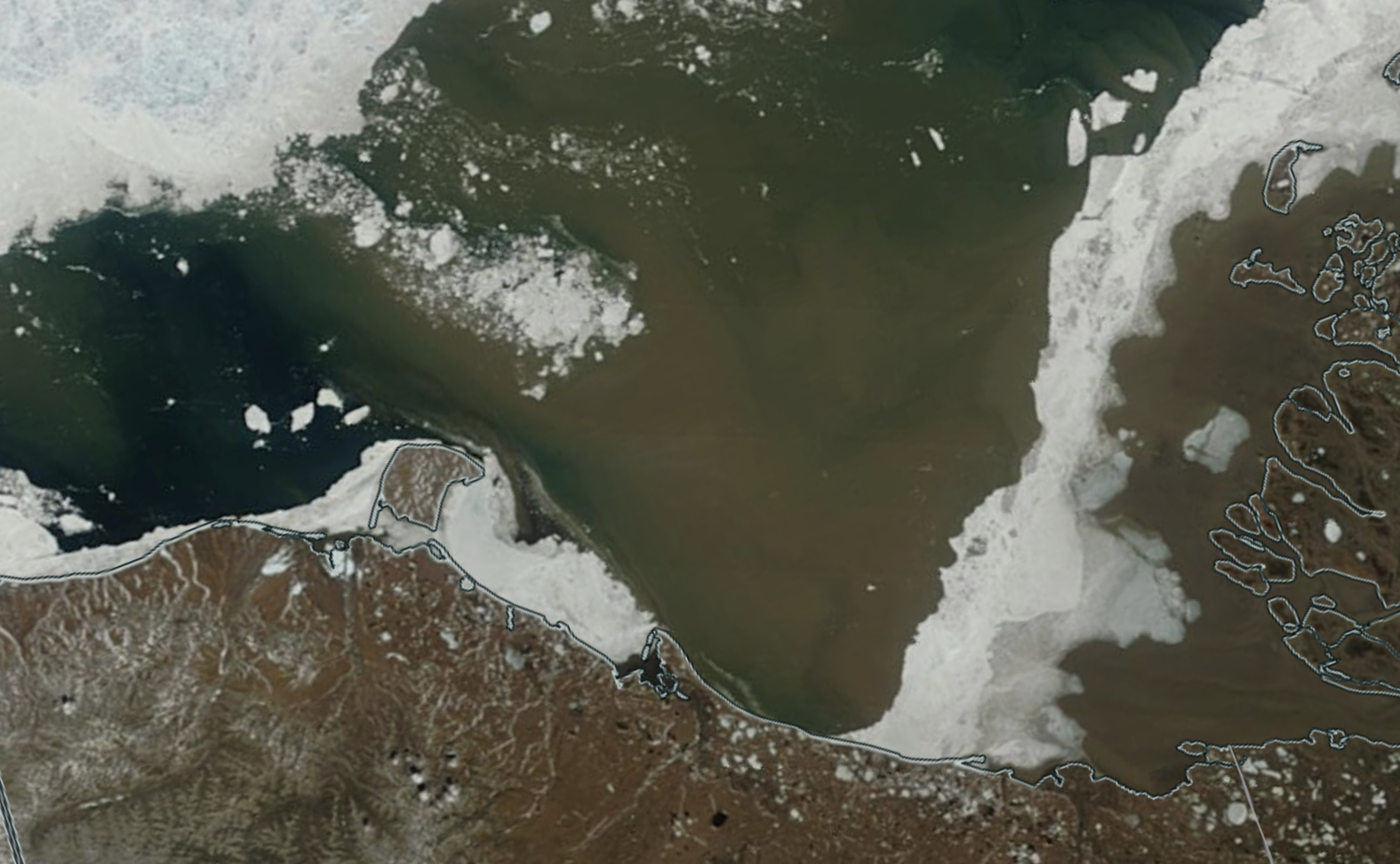

After a scenic flight across the Yukon and over to the Mackenzie Delta, we landed in Inuvik, where we would spend the next week doing more logistics. Originally scheduled to fly to Qikiqtaruk on June 17th, our timeline became uncertain due to the icy conditions on the Island. We soon discovered that Qikiqtaruk was experiencing the highest spring sea ice cover in over 20 years. So our imminent departure to the island was going to be delayed.

This is one of the latest sea ice years since around the year 2000 on the Yukon North Slope. Satellite images of the sea ice concentration around Qikiqtaruk on 11th June 2023 and 11th June 2024. NASA Worldview.

Although this news meant that we wouldn’t be able to reach the island for some time, we were excited to use our newfound days to enjoy Inuvik’s balmy 15°C weather and explore the town’s attractions. We braved the water at Airport Lake as our first Arctic swim, and we practiced our northern plant and wildlife identification using our favourite app, iNaturalist (see above). Despite more time available, we still ended up working all day and much of the night to prepare for the field.

The team takes their first Arctic plunge in Airport Lake. Though the video doesn’t show it, Isla did take a dip and Elias did in fact succumb to peer pressure and dunk his head when the camera was off. Video by Isla Myers-Smith.

We even got the chance to stop by Richard and Tracey’s house for a hockey and nachos night. Richard is the Senior Park Ranger for Qikiqtaruk – Herschel Island Territorial Park and Tracey is the manager of the Capital Suites in Inuvik and former deputy chief of the Vuntut Gwitchin in Old Crow. We learned that when Richard isn’t working, he’s busy playing the guitar and singing songs about Qikiqtaruk, Aklavik and life in the North. As it turns out, our crew is very musical and we joined in on the jam session (with varying degrees of proficiency) on the keyboard, harmonica and spoons.

Time in Inuvik was mostly Arctic science logistics, but there was some time for playing music, eating nachos, hockey game watching and walks through the boreal forest. Photos by Isla Myers-Smith (left and centre) and Elias Bowman (right).

To our excitement, Tracey gifted us a lettuce plant from her beautiful garden to bring to the island called Jr. Shrub (though an Asteraceae and not a shrub to clarify), who is still our constant companion out here in the Arctic. Combined with our unlimited supply of Country Time Lemonade, we now have all the vitamin bases covered – no scurvy for Team Shrub this year!

Ciara and Charlotte lovingly keep Team Shrub’s newest addition, Jr. Shrub, the northern-most lettuce in the Yukon, safe on the flight to Qikiqtaruk. Photos by Isla Myers-Smith and Elias Bowman (right).

The extra days also meant that we had more time to do some much-needed fieldwork preparation. One of our major tasks was to purchase and drill holes into PVC piping, which will be installed this summer as wells on Qikiqtaruk to gauge the water level for MSc student Micah’s Waterlogged Environment Land Loss (WELL) project. The Aurora Research Institute served as our workshop for the drilling of over 1500 holes, courtesy of Alex and Elias!

Drilling thousands of holes and calibrating in the fluctuating environment of the Signal’s House cabin, all in the pursuit of scientific accuracy and precision for the WELL project. Photos by Isla Myers-Smith.

On our second trip to Inuvik, a mere hour after landing we were in the tent in the centre of town for the 55th Annual Northern Games. The Northern Games is a gathering from the Inuvialuit Settlement Region to across the Canadian Arctic, Alaska and around the circumpolar Arctic, where people come together to participate in traditional games of agility, strength and pain tolerance.

The muskox push (left) and two foot high kick (right) at the 55th annual Northern Games in Inuvik. Photos by Isla Myers-Smith.

We have had a go at some of the Northern Games on the island with rangers Gina and Phil. We are nowhere near as talented as the athletes we watched, but having a go at the high kick or the musk ox push, gives you a real appreciation for the skill involved. We got to watch our intern Gabrielle compete in the musk ox push and ranger Craig compete in the one foot high kick. In a summer, when the Olympics is just beginning in Paris, France, for us the Northern Games was a chance to immerse ourselves in the sports of the Arctic.

Rangers Gina and Phil and Team Shrub practicing northern games including the high kick, leg wrestling and the musk ox push on Qikiqtaruk. Photos by Isla Myers-Smith.

Chasing cargo shipments is a key part of Arctic science logistics. Our re-routed acoustic recording equipment arrived in Inuvik just in the nick of time thanks to the Grabowksi’s of Whitehorse who cargoed our package north to us! Thanks for saving the day yet again Tony and Patti! On our second trip it was an even tighter cargo arrival. At AirNorth Cargo in Inuvik, Micah only had time to say “PVC now!” before grabbing our missing PVC and running back to the Aklak hanger and jumping on the plane.

Our re-routed cargoed equipment arrives in Inuvik just in the nick of time before the charter flights. Photos by Isla Myers-Smith (left) and (Micah Eckert).

On both of our trips to the island, our time in Inuvik came to an exciting – albeit abrupt – end on when Isla informed us that there was a small possibility of flying out sooner than we were scheduled to fly. She had received word that the airstrip on Qikiqtaruk was ice-free enough for the Twin Otter to land, but only if the fog continued to hold off. This was an exciting prospect for us, because we had been discouraged by satellite imagery showing uninterrupted sea ice on all sides of the island. Having expected to depart many hours later, we still had a significant amount of packing, food purchasing, and hole drilling to do.

Packing chaos, last minute cargo deliveries and expert box packing are all a part of Arctic science logistics on Team Shrub. The final days and hours in Inuvik are usually some of the most stressful, but if you can survive that, you can survive any part of Arctic fieldwork. Photos by Isla Myers-Smith.

We scrambled to finish all of the last tasks and raced off to the airport as soon as we got confirmation that we could fly. Our crew are now seasoned experts in last minute flight logistics. In true Team Shrub style, we were in the air 20 minutes after arriving at the airport and off on our next adventure out on the icy tundra landscapes of Qikiqtaruk. On our second trip it was a similar situation as we were chasing the arrival of a big low pressure rain storm on the coast. We arrived at the airport a mere 15 min before the plane doors closed and 20 min until take off and that included the packing of the plane! Epic. No one knows Arctic Logistics better than Aklak Air!

No one knows how to pack a twin otter better that Aklak Air. They can go from the truck to the a fully loaded plane in about 15 minutes! Photo by Isla Myers-Smith.

We’re back in the Arctic or up in the mountains of the southern/central Yukon and our Arctic field logistics are over for now. Once you are all set up at your Arctic field site with all of your food, supplies and equipment and you can’t think of anything that you have forgotten, it is a wonderful feeling.

Finally, once the bags and boxes are backed and out at the hanger all weighed for the flight and you get that call that it is time to fly. You load onto the back of the Twin Otter, taxi along the runway and then you’re airborne and your stresses fall away. Then after an hour flight and an often exciting landing on the beach airstrip, you step on Qikiqtaruk and know that you are there and the science can begin!

The first view of the island from our return flight to Qikiqtaruk after two weeks for the Arctic Crew in the Southern Yukon. To get to this point in the summer, you need to do A LOT of Arctic science logistics… Video by Isla Myers-Smith.

… that is until the end of the summer when the Arctic science logistics starts up again for the close of the season and we have to do A LOT of inventorying and repacking. Sigh.

Words by Charlotte Mittelstaedt, Isla Myers-Smith and the rest of the team.

The Arctic Crew of Team Shrub lands on the island on the 26th July 2024 as the Alfred Wegener Institute Crew leaves the island. Photo by Isla Myers-Smith.