At the June 2018 Google Earth Engine User Summit in Dublin, Ireland, 200 people came together to learn how to use the Google Earth Engine – a planetary-scale geospatial platform – to reshape our understand of the planet. One of the most exciting things about the three-day user summit was all of the people that we all got to meet from different walks of life, representing different disciplines, organizations and career stages. In the following blog post, we highlight six women using the Google Earth Engine to improve our understanding of global change impacts and make a difference for people around the planet.

Isla Myers-Smith

Chancellor’s Fellow and Senior Lecturer at the University of Edinburgh

https://teamshrub.com/

Satellite datasets indicate a substantial greening trend in the rapidly warming Northern reaches of our planet. Field scientists like myself have also observed vegetation change at sites around the tundra. The satellite greening pattern is thought to be caused by this on-the-ground vegetation change, but when we compare the satellite greening observed in pixels the size of farm fields or football pitches with the vegetation change observed in 1 m squared plots, we don’t always see these patterns matching up.

One way to figure out what specifically is causing the greening trends observed in satellites is to add higher resolution data into the mix using drones. Drones can carry sensors that are similar to those on satellites, yet they provide imagery below the clouds and at very high resolutions with pixel sizes of centimeters instead of meters or kilometers.

Ever since I first got the opportunity to visit the Arctic over 10 years ago, I have been fascinated with how this temperature-limited biome at the extremes of our planet is rapidly responding as the planet warms. The Arctic is warming at twice the rate of the rest of the world and the impacts of that warming are already being felt from thawing permafrost soils to increases in shrubs. All these changes could create climate feedbacks that could accelerate warming not only in the Arctic but for the Earth as a whole.

The Google Earth Engine provides the platform that will allow us to integrate analyses of satellite datasets with the high-resolution drone data that my collaborators and I are collecting at sites across the Arctic (https://arcticdrones.org/). At the 2018 Earth Engine user summit, I led a hackathon to explore how we can integrate drone data into analyses of satellite datasets and change in the Arctic. In just four hours, we made huge progress towards the analyses that will allow us to explore what is driving the greening of the Arctic and better predict how tundra ecosystems will respond as the planet warms.

Our drone hackathon app that allows users to explore what landscape level features such as bare ground patches might best explain when drone and satellite datasets don’t match up. This app was produced using the Google Earth Engine at the 2018 User Summit in Dublin, Ireland.

Gergana Daskalova

PhD Resarcher, University of Edinburgh

https://gndaskalova.com/

Land-use change is the most significant driver of ecosystem change around the world (IPBES reports), yet its effects on temporal trends in populations and biodiversity have not yet been quantified on a global scale. We don’t yet know to what extent all of the impacts that humans have had on the planet’s ecosystems have translated into the losses and gains of species at sites all around the world.

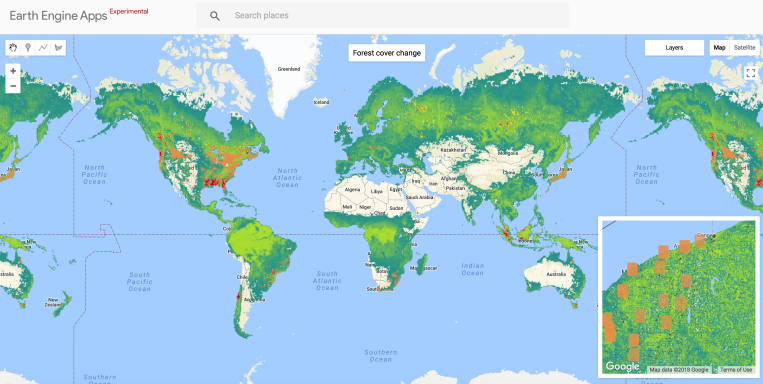

By synthesizing global datasets of temporal trends in global change drivers and the biodiversity of ecosystems, we can test for the relationship between the magnitude and timing of for example forest cover change and the populations and communities of the Earth’s biota.

My passion for quantifying land-use trends stems from having observed marked differences in land cover around my home village in Bulgaria, Tyurkmen. During my PhD at the University of Edinburgh, I am extending my personal knowledge of land-use change from my homeland to the global scale. I am integrating the global BioTime dataset with records of land-use change including forest loss and gain and conversion from forests to agriculture and also agricultural abandonment when nature takes over again.

The analyses required to test the link between biodiversity and land-use change are very computationally intensive. Attending the Earth Engine Users Summit allowed me to advanced my skills, so I can now extract information from global remote-sensing databases, quantify land-use change through time, and visualize the intensity of global change drivers around the world. This training is putting me one key step closer to understanding the impacts of humans on the biodiversity of planet Earth.

This app illustrates forest cover change at sites around the world where biodiversity monitoring is being conducted. My research will explore the attribution of biodiversity change to land-use change including the loss and gain of forests around the world.

Lauren Fregosi

Data Scientist at the Arnhold Institute for Global Health

MPH, Epidemiology Student at the Icahn School of Medicine

Understanding the ways climate, environmental factors, land change, and resource use effects the health of people around the world is critical to improving the health and well-being of communities and earth’s ecosystems. Specifically, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) serve as a guideline to ‘transform our world’ into a better and more sustainable global environment for everyone. Some of the SDGs that reflect my work in global health and epidemiology are ‘good health and well-being’, ‘clean water and sanitation’, and ‘climate action.’

With the ease of accessibility to global data, understanding the interaction of environmental variables and infrastructure variables on human health has never been easier or quicker. Google Earth Engine (GEE) has allowed for a quick and easy way to render all the data needed to respond to global health challenges in a timely and scientifically rigorous manor. I am able to use the comprehensive data catalog provided in GEE to analyze health trends and export such results into other platforms for further analysis in an uncomplicated and reproducible way.

My fascination with technology and my passion for improving health around the world have always been at odds with one another, fighting for the front row. There seemed to be a gap between the two; health workers studied one thing and engineers studied the other. Earth Engine bridges the divide between health research and technology to give researchers a tool that integrates the two fields seamlessly, resulting in a better understanding of global health dynamics.

Liza Goldberg

Intern at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Biospheric Sciences Lab

Student at Atholton High School

https://mangrovescience.org/

Mangrove ecosystems hold high ecological and economic value in coastal communities around the world. They provide key ecosystem services including coastal protection of communities during storms, biodiversity harboring, support of fishing-based economies, and high sequestration of carbon. However, nearly half of Earth’s mangroves have been lost over the past 50 years due to pressures ranging from aquacultural and agricultural growth to urbanization, extreme weather, and erosion. In order to prevent such losses from continuing, it is necessary to develop a real-time monitoring system with the capacity to track mangrove loss and degradation in vulnerable regions. A lack of such a monitoring system limits the ability of coastal communities to best preserve surrounding mangroves for their ecosystem services and ecological benefit, further limiting the scope of informed restoration and policy measures.

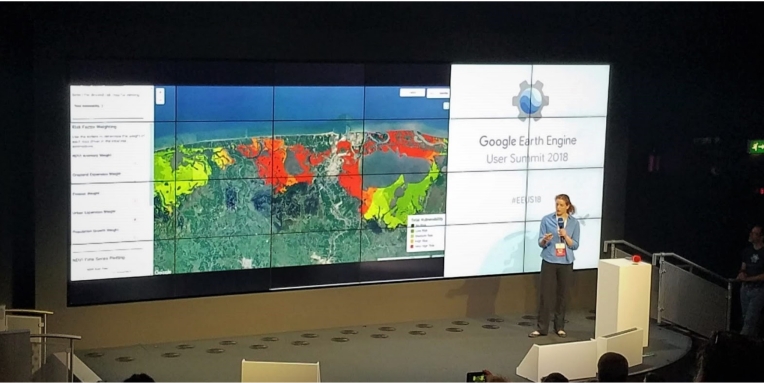

EcoMap, the Electronic Coastal Monitoring and Assessment Program, is an interactive portal that allows users to map and monitor global mangrove vulnerability and loss in real-time. Using Earth Engine’s capacity to efficiently aggregate satellite data from a variety open-source datasets, EcoMap quantifies risk for both anthropogenic and ecological loss drivers, including urban expansion, agricultural and aquacultural growth, precipitation, and erosion. Through an interface developed entirely in Earth Engine, users have the ability to evaluate maps for each individual mangrove loss driver, analyze total mangrove vulnerability estimates, track changes in forest greenness over time, weight each loss driver when calculating total mangrove vulnerability, and evaluate the proportion of vulnerable forests in each mangrove-holding nation. Earth Engine provides the ideal platform for programs like EcoMap that seek to bring satellite-based analysis to non-expert users around the world.

After finishing a science fair project that sought to evaluate the impact of climate change on red maple sampling carbon fluxes, I was presented with the opportunity to work with a group of mangrove researchers at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center at age 14. Around that time, several news stories broke about recent extreme mangrove losses in the Gulf of Carpentaria region of Northern Australia. Several thousand hectares of mangrove forests were lost within a two-year period, and I was surprised that no system existed to predict and monitor the risk for such immense losses before they occurred. To solve this problem, I began developing the EcoMap platform in Earth Engine to serve as a global means of real-time mapping of mangrove vulnerability. I have continued building EcoMap since, and look forward to bringing the program to communities in several East and West African nations to monitor local mangrove loss and risk. Using EcoMap, I hope to promote sustainable use of such vital ecosystems, ultimately preventing the recurrence of such extreme die-offs in the future.

The GEE Summit breakout sessions allowed me to learn several key methods for object-based classification and land use change analysis, both of which I can use to better predict the effects of growth of particular stressors on mangrove degradation and loss. The summit also gave me the opportunity to meet other researchers who may be interested in collaborating in the release of a final web-based/mobile EcoMap product. I was thrilled to both learn these new techniques to enhance EcoMap and network with other attendees who share a common interest in using GEE to bridge the gap between science and sustainable development.

Sabrina Szeto

Geospatial Analyst, Ucross High Plains Stewardship Initiative

Master of Forestry, Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies

http://highplainsstewardship.org/

The Ucross High Plains Stewardship Initiative is a research program at Yale which fosters science-based land management across the intermountain American West. We partner with land managers such as ranchers and conservation organizations to work on questions about wildlife habitat, soil carbon, invasive species and achieving management goals for working lands. As a geospatial analyst, I make maps and build tools using both field and earth observation data to answer those questions. I also work closely with graduate students to help them harness the power of platforms like Earth Engine for their own research. At this year’s summit, I presented a lightning talk on how we are building a community of Earth Engine users at Yale University. We are doing that through a combination of peer-teaching, outreach and student mentorship in collaboration with a graduate course on geospatial software design taught by Professor Dana Tomlin.

I want to use geospatial analysis and earth observation data to tackle social and environmental challenges. As someone who studied both anthropology and forestry, I am curious about the way natural and social systems interact, and how human values impact the management of ecosystems. We live in an era of unprecedented change and resources as the increasing amount of data and processing power available makes new questions and new answers possible. Anyone with an internet connection can calculate global forest loss by year with a few lines of code on Earth Engine. Seeing the wide variety of challenges that are being addressed by developers on Earth Engine gives me hope that we can actually beat the tide on these issues. How? By turning data into useful information that can be acted upon by decision-makers.

I was particularly excited about now being able to publish apps built using the Earth Engine User Interface functionality with the click of a button. This will extend the impact of our tools as it has made updating and maintaining them a lot easier. Land managers who may not be expert GIS users or programmers can now easily access the results from our tools. I was also glad to see the interest in starting up other user groups in other organizations and universities, and have been in contact with other fellow conference attendees who are leading such initiatives. Seeing people take the new skills they learned during the conference and implement them into prototype solutions during the hackathon was inspiring to me.

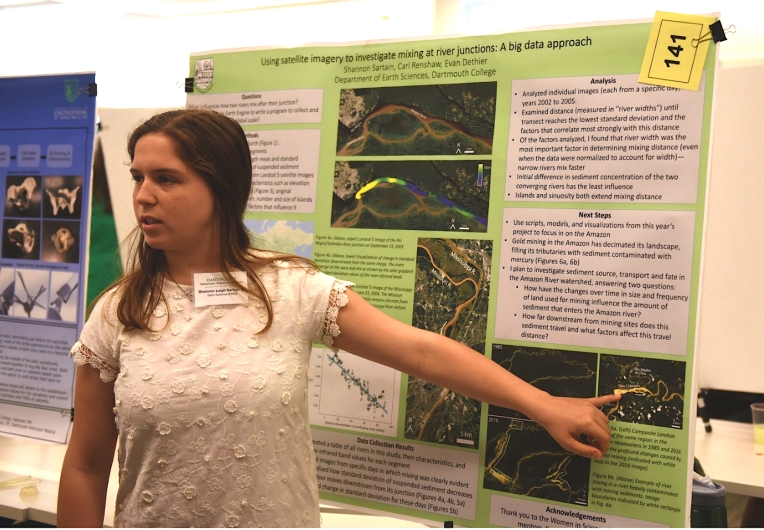

Shannon Sartain

First-year university student

Earth Sciences Department, Dartmouth College

For my independent project at Dartmouth College, I study river mixing: when two rivers carrying different amounts of sediment join, how do their waters mix downstream of their confluence? Next year, I will use the skills and knowledge I’ve gained to investigate gold mining in the Amazon basin. Miners remove sediment from the rivers and add mercury to it because it bonds with the gold, allowing it to be extracted. When the sediment is returned to the river, it contains mercury which then can be taken up by fish in the river. This is a critical problem to address because fish are an important food source for those living in the Amazon basin.

Earth Engine— obviously, but, most notably— allows for data analysis on completely global scales. For my introductory research project, I have been able to amass data from rivers all over the world; Earth Engine allows us as researchers to make very broad statements about our planet’s processes (or anything else under investigation) because of the magnitude of not only data accessible, but also of its processing power. I have learned that the Earth Engine is more than just a tool to use for research but an interface embedded in a network of users, from whom I have already learned so much.

As I have been making my entrance into the scientific world, I have learned more about the inner workings of the research and publication processes. What it takes to get grants approved, the mechanics and biases of peer review, and the ultimate quest for publication. I understand it can be easy to get caught up in these details and, in a way, pursue science for science’s sake. However, I hope to continually acknowledge the power science has for change and use it for bettering our planet, whatever that might look like in my future. The problem of mercury infiltrating the waters of the Amazon basin is very real and dangerous for a large population of people. I look forward to continuing this research with more than just a publication in mind – with the goal to make an impact through my research.

I am very inspired to see how so many women are carving their paths through the scientific community. I am fortunate that my school has a fantastic Women in Science Project that allowed me to gain exposure to geospatial data analysis and the Earth Engine. That being said, the department in which I research and my group of mentors are both very significantly male-dominated. I have been fortunate to receive only support from those I work with, but to speak very personally with many women at the conference allowed me to believe more in what I am capable of accomplishing. In a way, I know this positive experience at the summit will help me achieve academic goals in my future— it will never fail to empower me, reminding of our capabilities as scientists.

At the Earth Engine User Summit, I got to meet the very people who created this beautiful tool – a very unique experience and a chance to ask questions or provide feedback. However, as a researcher very early in my scientific career, the most important thing I gleaned from the conference was meeting the other amazing women (#GalsofGEE) and speaking and sharing about our experiences and women in science.

by Isla, Gergana, Lauren, Liza, Sabrina and Shannon