Last week we all applied for our own job.

Well, sort of.

In preparation for this week’s lab meeting on CVs and job applications, Isla asked us all to apply for the position of Team Shrub lab manager. The job is unfortunately fictional for all of you getting excited out there, but here is what we received in our inbox on Tuesday morning.

**********

Data/Field Manager position on Team Shrub

Team Shrub at the University of Edinburgh, a dynamic and friendly research group focussing on global change ecology, is hiring a lab and field data manager. We are looking for someone with data management skills including experience programming in R and using statistics such as hierarchical modelling. Experience in version control using GitHub would be an asset. The position will also involve fieldwork in the Canadian Arctic. Some outdoor experience is a requirement and any background leading or providing logistics to expeditions would be an asset. We are looking for applicants familiar with computers, scientific data and ecological fieldwork. Diverse applicants from a range of backgrounds are encouraged to apply. To apply please bring a 1-page CV to the next lab meeting to be discussed by the job application committee. We will be in touch with all qualified applicants to set up an interview. Application deadline: Friday, 3 November 2017 at 2pm. The job will be full time at a pay scale commensurate with the experience of the recruited applicant.

**********

And so we arrived, CV’s at the ready and slightly nervous, ready to discuss exactly what it takes to get your dream job. Here is a summary of our thoughts trying to encompass jobs from an undergraduate summer position, PhD or postdoc through to an academic job.

Some topics we didn’t necessarily all agree on – particularly with respect to the increasing importance of online content. But overall the general message applies across the board: you won’t get a job if you don’t apply, and putting in some advanced thought and work will put you in a much better position to submit a strong application when your dream job does come along.

Team Shrub’s Top Tips

1) The CV

The CV is the way that you communicate your skillsets and experience concisely to the rest of the world. It can be a very important document making the difference for whether you get considered for a job or not. Try to do your best to sell yourself in your CV.

- Keep your CV/job applications as up to date as you can – because you never know when your dream job might be advertised. You will never get a job or funding if you don’t apply, but try to put your “best foot forward” when you do submit those applications. Sometimes it is better to not apply for everything and target your time towards the jobs you really want.

- Update and restructure your CV/job application for every job that you apply for. Think about the key skills or set of experience that the job is looking for. Make sure your application is tailored to those skills and the specific job. Think about who is doing the hiring. And use the actual words in the job ad in your application. Make it clear that you have done your research and how specifically you are a good fit for the job.

- When comparing CVs, we thought that the ones with the skills sets really clearly indicated on the first page were most successful for a field assistant/lab assistant type job. This might be less important for an academic job when publications and funding might be most important. Tailor the content of a CV and the structure and formatting to each job you apply for making sure that the most important stuff always comes at the top and on the first page.

- You can format how you like but think about choosing an easy to read but nice font – feel free to choose something that you think does a good job of representing you! Try to use headings, lines and formatting to cluster the text into different sections. Use whitespace to your advantage – make sure you have a nice concise summary of your qualifications, but that you also don’t overwhelm your reader. People mostly skim CVs so you want the important stuff to really stand out!

- You should go back as far as seems relevant for the position you are applying for. Try to tailor the content, but when in doubt it is probably better to include something rather than leave it out. When you are in your undergrad, include your high school marks and awards. When you are a PhD student include your undergrad marks and awards. When you are a postdoc start to focus more on your PhD achievements and beyond.

- Include the information that makes you look more impressive or will make you stand out from the other applicants. You can include particularly high marks on courses or assignments that are relevant for the job you are applying for. You don’t need to include everything, but you do need to sell yourself. Never lie in a job application, but do be selective and edit your information to present the best version of you!

- Keep your CV to the appropriate length: 1-2 pages for most jobs, but can be much longer for academic CVs depending on your career stage.

- Don’t forget to include your name, email, address and other relevant contact information really clearly. Your age/birth date, citizenships, whether you have a drivers license or other personal information could be appropriate depending on the job/application.

- We thought that it is probably a good idea to include your referees on your CV, as this makes things more concrete and makes it look like you are confident about your referees’ assessment of you.

- Do consider including some other interests or less conventional elements to your experience. Are you an award-winning photographer? Do you write a well-read blog? Do you volunteer for a charitable organization? If so include that information towards the end of your CV as that might make your application unique and allow you to stand out from the other applicants with similar skill sets to you.

- Think about the file names for your CV and all other job application documents. Make sure it is something that identifies you and the date and perhaps the job as well. Submit all documents as PDFs, as the formatting of Word files can get messed up on different computers. Try to combine multiple documents in one application package. Include page numbers with the total pages (e.g., page 2 of 15) and put your name, the date, and other info in the header of each page, so that if anything goes missing it is easy to put your application back together again.

Shadow CVs: We all agreed that it’s very useful to look at other people’s CVs, especially as an undergraduate and early career researcher, to get an idea of what to include and what formatting to use for different types of job applications. Looking at other people’s achievements, though, can sometimes get you down, as we inevitably compare ourselves to others. A few years back, people started talking about shadow CVs as a way to show that people do fail sometimes, and that’s okay. A shadow CV is a record of all the positions you didn’t get, your unsuccessful grant applications, etc. Tenured scientists shared their shadow CVs online as a way to show early career people that failure is part of the process. Some have even went as far as suggesting we should have rejection goals – one can ask, if we are never getting rejected, are we aiming high enough?

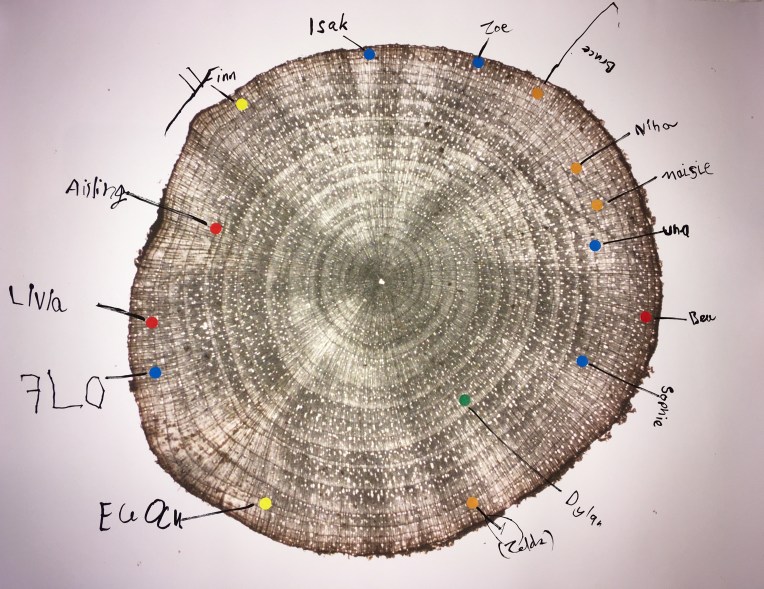

An example of Haydn’s CV, applying to be on Team Shrub

2) The Cover Letter

The cover letter allows you to express why you are applying, why you are passionate about the job, and why you are the best candidate out there.

- Always submit a CV and cover letter unless you are explicitly asked not to, even for applications for PhDs or Postdocs. It probably won’t hurt your application, and it might really help!

- Write your cover letter on letter head or format it professionally. Include your contact information, the date and an electronic signature.

- Always address your cover letter in a gender neutral and appropriate way. Try to address it to the specific person who is doing the hiring. If in doubt, use something generic like “To whom it may concern:” or “Dear Colleagues,”.

- Start the letter off with a very short generic paragraph explaining what you are applying for. Indicate that there are 3 (or more) reasons why you are highly qualified for the position.

- Have a series of short paragraphs with clear numbered headings on each of those reasons (e.g., “Track record of high-impact publications, Evidence of funding success, Commitment to teaching and mentorship” or “Experience with statistical programming, Three field seasons conducting ecological research, Evidence of leadership and independent working”, etc.). You don’t have to follow this structure, but it is an effective way to structure a cover letter that can be easily skimmed for key content.

- Finish with a short paragraph indicating your enthusiasm for the position and your willingness to answer any questions.

3) The online profile

A lot of the information about you that an employer, award committee or future colleague will access is now online. From LinkedIn, Google Scholar, Twitter, Facebook, and more we all have some sort of online profile now. Make sure you are in control of that online profile somewhat, putting out the content that you want people to associate with you.

- Google yourself. Your web presence might surprise you. Make sure to put private browsing on, so that your search engine is not pre-trained to find content about you. Some people are more Googleable than others because their names are more unique or they have a larger online profile. Think about what content you want to be linked with your name and whether your different websites or social media sites do justice to you. It is up to you how visible you want to be online with your own website and social media such as twitter. Over time slowly work towards making your online presence stronger to sell your skills and career niche better.

- A shout out to LinkedIn: we discussed LinkedIn and how it is a must for much of the business world, but isn’t used much in academia. Therefore, it is probably worth maintaining a LinkedIn page if you don’t know what career you will end up in or just to be on the safe side.

4) The website

Websites are critical if you are aiming for an academic career and are thinking of applying for fellowships or academic positions. We had some discussion about it, but some Team Shrub members feel that websites are now replacing the business card as the way people can find out your contact information and a bit about your job profile. Alternatively, for careers with large companies, you might want to keep your online presence quite minimal. If you are thinking about doing any independent consulting, starting your own business, getting involved in a start up, or going into communication in some form, your online presence is what will or will not get you the job/contract. Make sure to think about what you are putting on your website and online in general. Many (if not most) people will google you when hiring, they are looking for content that will impress them about you, but might also be influenced negatively by what they see online.

The Academic website is becoming a more and more important part of your profile as a researcher. I think that you should be looking to start to build your online content during your PhD, but potentially before. Think about how you are branding yourself and your research interests. Make sure to format your website in an eye catching and not too busy manner. Use beautiful photographs to illustrate the text. Keep things simple but relatively comprehensive. A website is always a work in progress. It doesn’t have to be perfect when you first post it. Build your branding, profile and online content over time.

- About page/team page: When building an academic website include a page about you with your professional contact information and a brief description about your research interests. Include a photo that is recognisably you, but make sure it isn’t too large or overwhelming or too small and unidentifiable. People will start to make assumptions about you from looking at your website, so you want to leave the right impression. Include any other members of your research team if appropriate. You want your website to appropriately reflect your career stage and to demonstrate the trajectory that you are on. For example, if you co-supervise dissertation or PhD students, put that on your webpage.

- Research: Include a page about your research interests – update this overtime to reflect your current interests. Think about how you want to pitch your own research. A lot of academic websites start with the statement “I am generally interested in a broad range of topics in ecology (and evolution).” This is a throw away statement. If you weren’t generally interested, then you probably shouldn’t be in the field. Start with a statement that is specific to you and sets you apart from other ecologists. Don’t include too much text here and do include pictures, conceptual diagrams, etc. Make it easy for someone skimming your webpage to know what your research is all about. Indicate your funding somewhere, particularly if you applied for that funding yourself.

- Publications: Include a page of your publications – try to provide some additional content here if you can about your papers and provide a link to your Google Scholar and ResearcherID/Orchid accounts, etc. Try to make it easy for someone visiting your website to get to know what your research is all about and also your publication stats, particularly if they are impressive for your career stage. Consider making in prep or submitted manuscripts available via your website using pre-print archives such as BioRxiv (https://www.biorxiv.org/).

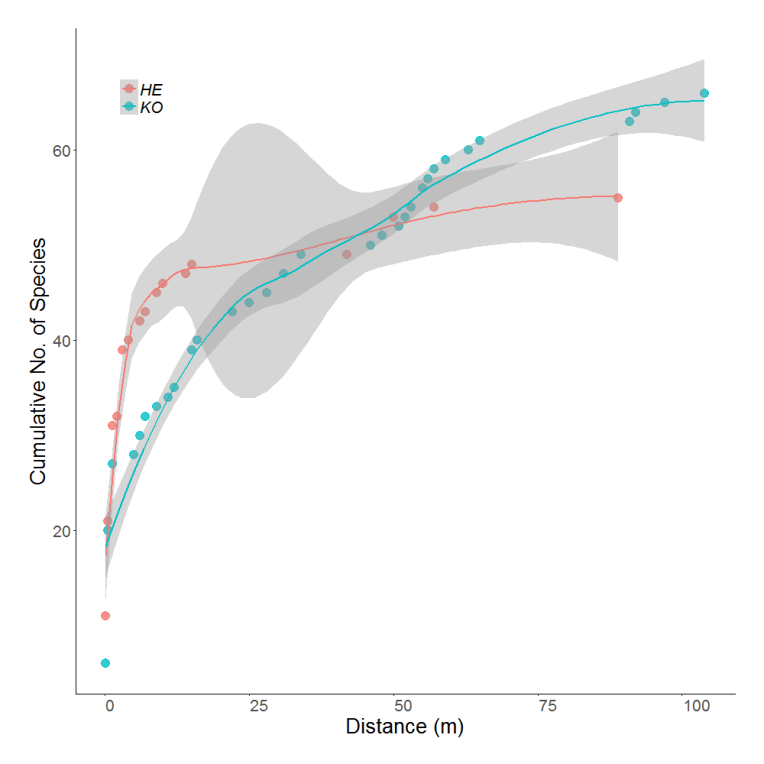

- Code/Data: In the world of open science, you will get bonus points for making your code and data publically available. I am always looking for evidence that people are participating in open science best practices when assessing job applications or research grants. Use your website to share this information with the world, though it is best to host your code in approved repositories (e.g., http://datadryad.org/) and your code in a version control platform such as GitHub (https://github.com/).

- Teaching/Outreach/Media/Social Media: Include a page or more than one about your outreach, engagement and teaching interests. These are becoming more and more important parts of the academic profile. If this is an area you have invested time in, make sure you do justice to that on your website, as it could set you apart from the other applicants for a job.

- Links/Networks: Consider providing links to relevant other groups that you are associated with – try and illustrate your professional network. Link to your collaborators or large research projects that you are associated with. Put your own track record into a larger academic context.

- Other stuff: Consider including other stuff on your academic website that isn’t strictly academic. If you do photography, if you make films, if you do art or music this can feature on your professional website if it contributes to your academic/professional profile.

5) Making contact

If appropriate, get in touch with the person doing the hiring in advance to ask about the position. Set up a Skype call if appropriate to introduce yourself or meet in person for a quick chat. Show your enthusiasm and demonstrate that you have thought carefully about the position and how you might fit into the group/business/organisation. Always get in touch via email before applying for PhD positions or postdocs that you are well qualified for – this will put you at a major advantage and most academics are expecting some sort of contact in advance of the actual application.

Think about that first email contact and make sure you demonstrate your specific interests in the position, but keep things brief and to the point for the first contact. Expect with busy people that you might not hear back right away. Feel free to contact them once again if you hear nothing after about a week, but if you still don’t hear back, perhaps this is not the job for you. Think about other ways to network with potential employers – like talking to people at conferences, meeting with the seminar speaker, getting in touch with lab members in the group, etc.. People are more likely to hire people they have met before or have some sort of established connection.

*

In summary, it is never too soon to start thinking about your academic or job profile and trying to put together that dream job application. There is still some debate out there about how best to sell yourself in our increasingly online world, but many things such as how to format your CV haven’t really changed much over time. If you have put some thought into your job application in advance, you are in a much better position to apply for that dream job when it comes along!

Oh, and we all got the job.

By Team Shrub compiled by Isla Myers-Smith and Haydn Thomas

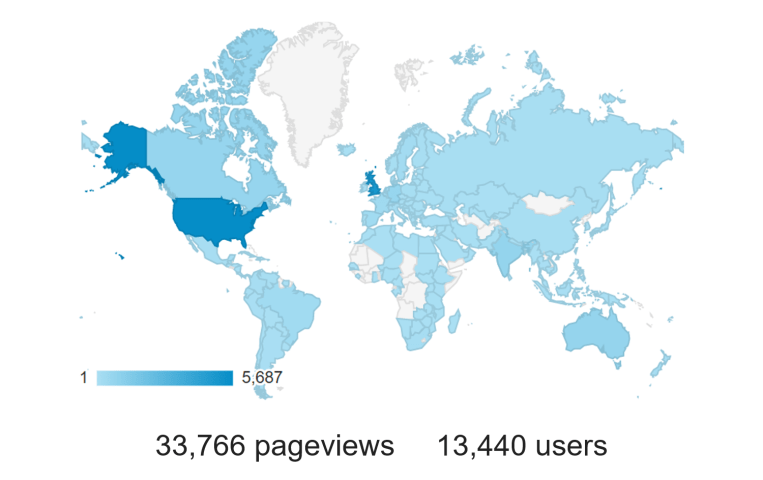

This November, we are celebrating Coding Club’s first birthday – one year full of workshops, lots of code and many moments of joy as we finally figure out how to get our code to work and improve our quantitative skills together! It’s been such an exciting year, and we are thrilled to see many new faces joining us, as well as familiar faces returning workshop after workshop.

This November, we are celebrating Coding Club’s first birthday – one year full of workshops, lots of code and many moments of joy as we finally figure out how to get our code to work and improve our quantitative skills together! It’s been such an exciting year, and we are thrilled to see many new faces joining us, as well as familiar faces returning workshop after workshop.