It’s been 18 days on an Arctic island and just over a month above 60°North. Team Shrub has faced every element, from sub-zero temperatures to Arctic heat, storms, bugs and wildlife. But, what brings us North? In this blog post, we will introduce you to our Team Shrub crew, give you insight into this year’s research, and bring you along on our adventures so far in the field season.

Midnight sun in Kluane. Photo by Alex Beauchemin (left). Midnight sun on Qikiqtaruk. Photo by Isla Myers-Smith (right).

As the North continues to experience a rapidly changing climate, extreme weather events are predicted to increase in frequency, fundamentally altering the lives of plants, animals and ultimately people. Team Shrub is working to understand how tundra ecosystems are responding to these changes. This summer’s research will help us figure out how the above and below-ground responses of tundra plant communities ripple across food webs to insects, birds, and mammals, and how Arctic heatwaves reshape permafrost landscapes. What will a later summer – in contrast to recent years -mean for the timing of plant and animal life here on Qikiqtaruk and down in Kluane? Only time will tell. Stay tuned to find out.

This summer, we’re launching the fieldwork of the Canada Excellence Research Chair on ‘The Global Ecology of Northern Ecosystems’, continuing our work on the NERC TundraTime project, the RESILIENCE Synergy grant, the Porcupine Caribou Knowledge Hub Project, and beginning the field asset collection for National Geographic Society Funded ‘Communicating Arctic climate change impacts using immersive virtual reality’.

This past year saw the transition of Team Shrub from the University of Edinburgh to the University of British Columbia. Led by Isla, this year’s field crew consists of three undergraduate students, three recent graduates and two masters students who will join the team in July. With many in Team Shrub new to the Canadian Territories and the Arctic, the extended hours of summer daylight and cooler temperatures of Northern life are a first-in-a-lifetime experience. Once again, this year’s field crew is split between Team Southern Shrub, in the Kluane Lake Region, and Team Northern Shrub, on Qikiqtaruk – Herschel Island.

Tundra Time

Capturing tundra phenology above and below ground in a warming Tundra

This is the final field season of the Tundra Time project. This project takes place at both of our field sites on either side of the Yukon Territory. In Kluane and on Qikiqtaruk, we’ve got the phenocams all set up to measure the timing of plant growth across the summer. And, in the coming days we will be removing the first of this summer’s in-growth cores to measure the timing of root growth below ground. With two teams working at two sites, our work on this project can progress in tandem. If you want to get a sneak peak of the results of this project, check out Elise’s (Dr. Elise Gallois, that is) new preprint ‘Tundra vegetation community, not microclimate, controls asynchrony of above and belowground phenology’.

KLUANE LAKE – Team Southern Shrub

Team Southern Shrub consists of Anya and Lauren, both recent UBC Environmental Science and Sustainability graduates. Before joining the team, Anya has three seasons of tundra field experience under her belt and Lauren has done participated in climate change research and advocacy.

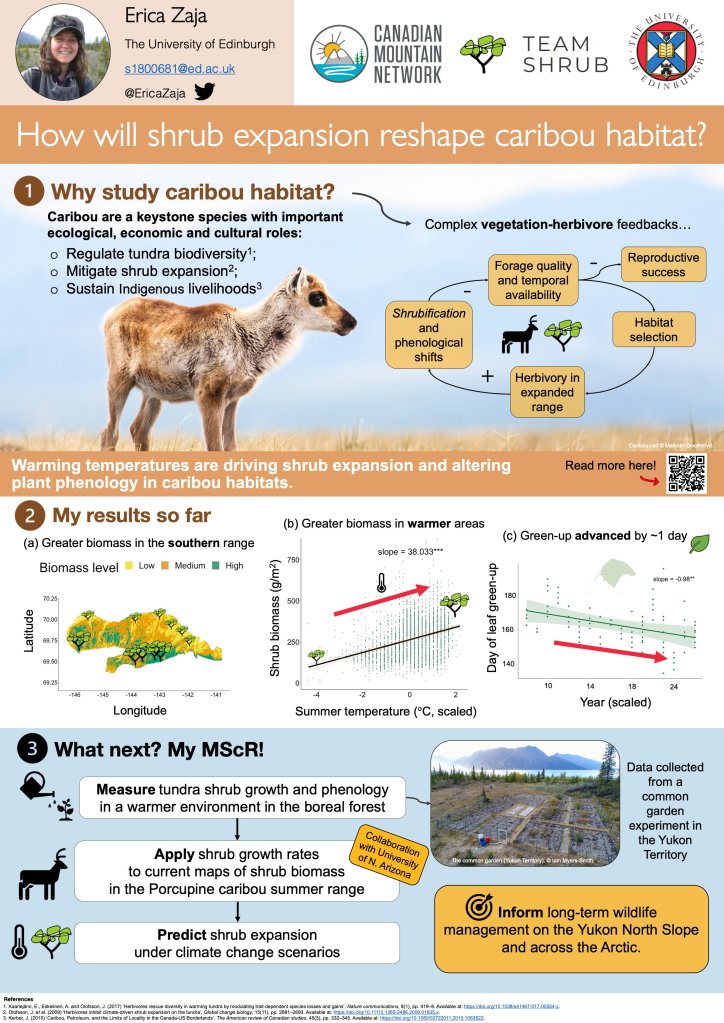

At Kluane Lake, the common garden experiment continues for an eleventh year. Common garden experiments involve collecting plant individuals from geographically differentiated populations and growing them together under shared conditions. Set up by Team Shrub in 2013, the Kluane Lake common garden is used to determine the growth rates of three key willow species driving alpine and Arctic shrubification (Arctic willow – Salix arctica, Richard’s willow – Salix richardsonii and Diamond Leaf willow – Salix pulchra) under warmer climate conditions than where their source populations were located.

Team Shrub on the Kluane Plateau. Photo by Ciara Norton (left). Anya and Lauren on the top of the Plateau. Photo by Lauren Moody (right).

Arctic shrubs from Qikiqtaruk – Herschel Island (70°N) and alpine shrubs from the Kluane Plateau (61°N) were transplanted into the warmer environment of the Kluane Lake Region, well within the boreal forest – an environment which experiences summer temperatures 3-5ºC warmer than either source environment. The common garden helps inform predictions of shrub growth and phenology as the climate warms. Do willows grow longer and larger under warmer conditions? Or is willow growth restricted by genetic adaptation to local environments?

On the Kluane Plateau, we are studying patterns of seed predation along an elevational gradient and contributing to a cross-continental study spanning the Americas. How do patterns of seed predation vary with elevation and latitude? We’re carrying out the protocols at the northernmost site in this experiment to find out. Preliminary findings confirm that seeds are eaten to a greater extent at lower latitudes, indicating greater pressures on plant reproduction towards the equator versus at higher latitudes.

PikARU Project

Monitoring Pika Abundance with Autonomous Recording Units

Undergraduate thesis student Charlotte will be joining the Arctic crew for the first Qikiqtaruk trip before migrating to Kluane for the remainder of the field season. New this year for the Kluane team is the PikARU Project, led by Charlotte in collaboration with the Environmental Sustainability division of the Government of Yukon. Collared pikas (Ochotona collaris) are small mammals that have been designated a species of Special Concern by COSEWIC due to their sensitivity to environmental change.

Pikas are the inspiration for Pikachu, hence the project title “PikARU.” Shrubification may pose risks to the species because it has the potential to remove their preferred forage plants – forbs and graminoids – but the population-level response of pikas to vegetation change is unknown. Our crew will use autonomous recording units (ARUs) to study collared pikas in the Southern and Central Yukon, capturing the small mammal’s “meep”-sounding vocalizations. This will give us an idea of the abundance of pikas at each of our research sites. Could ARUs be a key tool for monitoring pika population health over time as they experience the effects of a changing environment?

QIKIQTARUK – Team Northern Shrub

In the Arctic, it’s been a chilly start to the 2024 field season. After the exceptionally warm summer of 2023 in the western Arctic, spring of 2024 was marked by the highest June sea ice cover along the North Slope of the Yukon in over two decades. We’ve been surrounded by sea ice for the first weeks of our field season. The cooler temperatures are atypical, and spring is around three weeks later than in recent years.

Up in the Arctic, Team Northern Shrub is continuing its monitoring of tundra plant responses to climate change. We’re using long-term plots to monitor changes to plant traits, phenology, and community structure. We’re also continuing the upkeep of our muskox-beloved phenocams. In recent days, the temperatures have warmed. The snow has been melting, the sea ice is moving offshore and summer has arrived. To keep up with the changing seasons, we’ve been running around the tundra capturing the timing of plant growth and pollinator and bird activity with wildlife cams, autonomous recording units and phenocams.

Here on Qikiqtaruk, with the delayed summer, early season plants are only just starting to flower. These Arctic gems are rare sights, often having already completed their life cycle by the time Team Shrub arrives. Being here for the very start of spring means that this year, we can capture the full summer cycles of flowering plants, pollinators and birds. Will the remainder of the growing season be pushed back due to the later spring, or will plant phenology catch up? Only time will tell.

Tundra THAW Project

Tundra Terrain Hazards From Arctic Warming

Heat events associated with climate change have led to massive disturbance events in permafrost landscapes. In July of 2023, an extreme heat event on Qikiqtaruk led to the formation of over 700 landslides across the island. These landslides are called active layer detachments (ALDs) and occur when dramatic permafrost thaw triggers the active layer of the tundra to slide downslope. These landslides have left dramatic scars on the landscape spanning across the island.

Qikiqtaruk is also home to one of the largest retrogressive thaw slumps (RTSs) in the world, another form of mass movement which results from permafrost degradation. The incoming research data coordinator, Ciara, is leading a project that monitors permafrost disturbance across the island, through both mapping the progression of the RTSs and ALDs over the summer and characterizing their morphologies. What drives the occurrence of active layer disturbance events, and how do active layer detachments progress over time? Will the ALDs progress into RTSs?

Tundra BUZZ Project

Tundra Bumblebee Unoccupied Study of Zoophily Through Zooacoustics

Plant-pollinator interactions are a key part of Arctic food webs. Insect pollinators fertilize plants, allowing them to develop fruits and set seed. Berries feed wildlife, from migratory birds to muskoxen and caribou. Without pollinators, Arctic life would not exist in the way that we know it.

As tundra plant phenology shifts forward under a warming Arctic, how does pollinator phenology change? Is shrubification reshaping pollinator communities? The Tundra BUZZ Project aims to uncover the workings of Arctic responses to climate change at the insect scale. Undergraduate thesis student Alex will be investigating bumblebee activity and phenology in relation to plant flowering time through the use of ecoacoustics and wildlife cameras.

The TURTLE setup used by the Tundra BUZZ experiment and the BANQUISE Project on Qikiqtaruk (left). A bumblebee of the Arctic subgenus Alpinobombus covered in pollen from Salix richardsonii (right). Photos by Alex Beauchemin.

BANQUISE Project

Bird Abundance and Nesting on Qikiqtaruk Under Icey Seasonal Environments

Every year, birds flock to Qikiqtaruk – Herschel Island in the thousands to forage and breed. Climate change impacts which species, how many individuals and when birds are arriving and nesting on the island. Snowmelt date has been documented as a primary driver of bird and plant phenology, while sea ice dynamics also play an important role (see former Team Shrubber Meagan’s research!).

For birds on Qikiqtaruk, every variable plays just one part in a complicated story determining their life histories. Using historic and modern records, Elias is quantifying direct and indirect impacts of environmental variables on bird abundance and nesting timing. With the addition of audio recorders and wildlife cameras to existing observations within the park, Elias will be able to tease apart how breeding birds are responding to the warming Arctic.

A Lapland Longspur calls in front of an audio recording TURTLE device. Photo by Elias Bowman (left). Savannah sparrow chicks in their nest on Qikiqtaruk – Herschel Island. Photo by Isla Myers-Smith (right).

Masters students Sarah and Micah will be joining the team later in the field season. Sarah will be studying drivers of borealization in Kluane while Micah will be focused on flooding on Qikiqtaruk. Stay tuned for updates on their projects later in the summer.

As we work away on our research, we will also collect imagery, video, sound and 360 visuals to capture this rapidly changing tundra environment. These assets will contribute to the next phase of our National Geographic Society funded project ‘Communicating Arctic climate change impacts using immersive virtual reality’. We’ve recently launched a website for this project, and we’re keen to figure out how best to share Arctic climate change impacts through virtual reality.

For more information on how climate change is altering Arctic and alpine ecosystems across the Yukon, keep an eye out for more Team Shrub blog posts this summer!

Signal’s House standing by on channel six nine in the Canadian Arctic.

Words by Alex, Charlotte, Elias, Ciara, Anya, Lauren and Isla