Our Arctic field seasons are both long with the passing of 24 hour days and hard work out in the field and incredibly short. Now that the field season is over and summer has ended in the Arctic, we can reflect on our final days on the island and what we accomplished during the field season of 2017.

When you are in the swing of fieldwork, you are in a routine of “early” mornings and very late nights and long days out on the tundra. On Herschel time, you get up at the crack of 10 am and then work out on the field sometimes as late as midnight or later with bedtime at around 2 to 4 am. After each long day in the field, you colour in a few more boxes on the fieldwork plan of tasks accomplished, but there is so much left to do that you wonder if we will get it all done.

On Qikiqtaruk you are always at the mercy of the weather and no time more so than at the end of the season. As the tundra starts to turn yellow and brown, the temperatures start to decrease and the fog starts to roll in grounding drone flights.

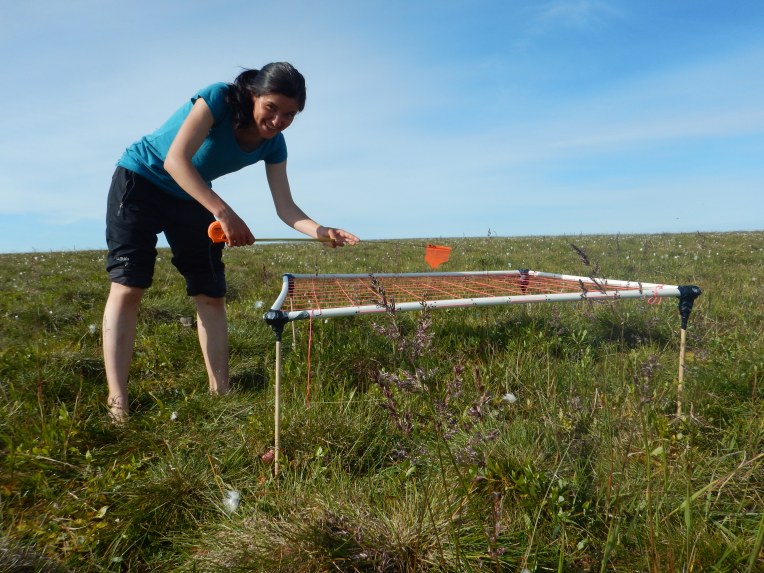

Storms are common in August and this August was no exception with a three-day storm overlapping with the date our charter flight was supposed to pick us up off of the island. That meant a day of being weathered in, but also a chance to do more last-minute data collection in the driving winds and rain. This year’s common garden samples might have been collected in pretty horrible weather, but here’s hoping those willows thrive in their new warmer home in the Southern Yukon.

This year there were some end of field season weather surprises for us. Unlike last year when the fog grounded our drone flights for more than a week. This year there were a few glorious days allowing us to get back to Slumps D and ABC to quantify permafrost thaw across the 2017 growing season. We were also able to complete a final round of multispectral flights over all of our tundra plots as the tundra was turning from green to brown and the plant phenology records indicated the yellowing of leaves and release of seeds. On the final glorious day before the storm, Andy and Will made it out to fly large extent flights of the Ice Creek watershed, allowing us to put our higher resolution data into a larger landscape context.

Just hours before flying off the island, we even managed to achieve one of the most elusive goals of the field season. It still feels slightly unreal, but after many attempts, involving finding different types of batteries, cables, Allen keys, screwdrivers, and building shelters to keep the rain out when taking the computer out into the field, we are finally happy to report success. We have downloaded all the data from our HOBO temperature data loggers, put in new batteries and restarted the data logging for the winter. These might all seem like simple tasks, but really, when you are out in the tundra, so many elements have to come together in order to achieve your goals!

Just when we had one HOBO sorted and ready to tackle the second one, we found out it requires entirely different tools to open it and cables to download the data. Because of the pouring rain, the process had a distinct Russian doll flair to it – a laptop inside a bin bag inside an emergency shelter inside a tarp.

On the morning of our last day, though, everything came together. Beautiful belugas accompanied us on our beach walk towards the data loggers on Collinson Head. We had all the tools we required (well almost), we even managed to improvise a radiation shield out of wooden skewers and medical tape to fix the broken one on that pole. And once we removed all the screws without dropping them in the pond below the logger box and plugged in the cable without getting it wet, the data were on our laptop in minutes! Yukon Parks conservation scientist Cameron Eckert was there to document the big moment – thankfully we are better at handling data loggers than high fives! It is a great feeling to leave your field site knowing that you have accomplished all of your fieldwork goals.

Though two months in the Arctic can seem like a long time when the data collection is going on, it is also a very short time. The end of the field season is when you begin to realize that your time on the island is coming to a close. You have your last walks across the tundra, last dinners with the community of people on the island and the last dips in the Arctic Ocean. This field season marks the end of the three-year ShrubTundra project. We have lots of data analysis and writing ahead, but no more data collection on this specific project. Sigh. Though the science never really ends!

We have learned an incredible amount over the past three years and it will be great to see all of that work come together, but it also brings us to the question of what research questions should we be tackling next. The work of a scientist is never done, as soon as you learn one thing, you are already thinking about the next question that you want to answer. Perhaps, through the HiLDEN network or other opportunities we will be able to explore whether some of the things that we have discovered at Qikiqtaruk-Herschel Island apply across other Arctic tundra locations.

Here are some of the preliminary research findings of the Shrub Tundra project research on Qikiqtaruk-Herschel Island:

- Plant phenology including the leaf out, flowering and to a certain extent leaf senescence is occurring earlier on Qikiqtaruk over the past 18 years as snow melts and sea ice retreats earlier (Qikiqtaruk Ecological Monitoring Team, in prep., Assmann et al. in prep., Lehtonen Ecology Honours Dissertation 2015).

- Plant biomass and height is increasing across the patches of monitored tundra and certain plant species are becoming more abundant including Eriophorum vaginatum (cottongrass) and Salix pulchra (diamond leaf willow), while other plants are found in the monitoring plots that weren’t there 18 years ago such as the grass species Alopecurus alpinus (Qikiqtaruk Ecological Monitoring Team, in prep.).

- Although plant heights are increasing community-level leaf traits such as the specific area of the leaves is not occurring very rapidly at Qikiqtaruk or other tundra sites (Bjorkman et al. in prep., Lowe Ecology Honours Dissertation 2015).

- Tundra traits differ from other of the worlds biomes and it is the traits of plants that link vegetation change to changes in decomposition and carbon cycling (Thomas et al. in prep.). That is why understanding how rapidly plant traits are change is key to understanding the implications of future tundra vegetation change.

- Qikiqtaruk willows can grow in warmer environments 1000 km to the south, but local adaptation to Arctic light conditions means that they are not growing as fast as their southern alpine counterparts in our common garden experiment that are really able to respond to the warmer growing conditions at the lower elevation down in the boreal forest.

- Climate is not always the factor explaining the variation in growth of shrub species from year to year on Qikiqtaruk, indicating that other factors such as deepening active layers and thawing permafrost releasing nutrients might be a driver of vegetation change (Qikiqtaruk Ecological Monitoring Team, Boyle Ecology Honours Dissertation 2017, Angers-Blondin et al. in prep.).

- Decomposition rates differ among microclimates, and soil moisture is just as important as temperature in explaining decomposition rates, but these differences are small compared to the differences between different types of plant litters (Walker Ecology Honours Dissertation 2017, Thomas et al. in prep.). As vegetation changes, so too might tundra decomposition rates.

- Analysis of drone imagery and 3D models indicates that tundra greenness is strongly related to topography and wetness of the landscape, but that this relationship depends on the scale of measurement. As permafrost thaws, this could lead to increased moisture where ice wedges are thawing and increased tundra plant productivity (Kennard Geography Honours Dissertation 2017, Assmann et al. in prep.).

- Rates of permafrost thaw and coastal erosion can be rapid and are associated with moisture in the landscape, with sometimes faster thaw rates in areas with water tracks or streams than in adjacent drier tundra (CBC article on high coastal erosion rates, Cunliffe et al. in prep.).

But these are just some of the results so far. Once we have analysed this year’s data in association with the data that we have collected over the past three years, we will really be able to put the story together of how vegetation is changing on this island in response to climate and environmental change and what that might mean for the future of this tundra environment.

After we made it off of the island after a one-day weather delay and a second day of ‘will we or won’t we fly’, we managed to make it back to the busy and bustling town of Inuvik where we had a few days of packing and inventorising. After getting all of our stuff organised and shipped back to Edinburgh or put into storage we had a chance to explore the MacKenzie Delta and town of Inuvik. Then we travelled down to Whitehorse and out to Kluane to bring this year’s common garden samples to their new boreal forest home.

Our arrival in Kluane meant the first reunion of the entire TeamShrub field crew for the field season of 2017. Finally, Team Drone could meet up with Team Kluane and share stories of our very different field adventures in the Canadian North. The reunion was celebrated with a party involving one last feast, music and even a magnificent show of the northern lights from green to pink rippling and dancing across the skies overhead. And with the final planting of willows in the common garden and a bit more storage and inventorising, our fieldwork was complete. Time for Team Shrub to have one (or several) last exploding high fives and to depart southwards and back to our other non-fieldwork lives.

Thanks Team Shrub for an amazing and incredibly productive field season! I can’t wait to see all of the data presents that will be revealed over the coming winter.

By Isla and Gergana