“Droning on about Arctic change” was a joke title that collaborator Jeff Kerby and myself came up with for a presentation recently, but it does actually accurately describe some of the research that we are doing here on Team Shrub. Nearly three years ago our research project – the ShrubTundra project, was funded by the Natural Environmental Research Council and that has given us the opportunity to get into the drone ecology business and travel for the past three summers up to the Canadian Arctic to bridge the gap between satellite and on the ground observations of vegetation. In this long-awaited blog post, I will tell you all about the drone research we have been conducting on the island, the new collaborations that we are building with drone ecologists around the Arctic and the preliminary results of our work thus far. Is the Arctic greening that satellites are sensing the same vegetation change that we observe on the ground? Here I go… droning on about Arctic change.

Much of drone technology has been out there for decades, including remotely controlled planes and military unmanned aerial vehicles, but with the commercialization of high powered batteries and the development of automated flight technologies, drones have literally taken off! In the past half-decade or so, the promise of drone technology for scientific research has begun to be realized and we hope that the ShrubTundra project is leading the way for drone ecology in tundra ecosystems. Drones are allowing ecologists to observe ecological processes at the landscape scale such as phenological changes, plant growth and community composition change. We have learned a lot over the past three years in our drone research and made some important discoveries so far, but there is much work to do. As we continue to collect terabytes of data out here in the Canadian Arctic, we can look forward to the data presents that will be revealed over the coming year.

The drone team up on the island is led by postdoc Andrew Cunliffe or as it says on his drinking glass – “Y Up”, and visiting researcher Jeff Kerby, “J-man the K-dog”. We are joined this year by drone pilot Will Palmer aka “Tool Bag”, our first commercial drone pilot on the team. Providing assistance to the team here on the island is soon-to-be PhD student “33 Thimbles” Gergana Daskalova, and me “Magnum PI” or “Captain Shrub” Isla Myers-Smith. And back in Edinburgh is our support team including PhD student Jakob Assmann, NERC Airborne GeoSciences manager Tom Wade, the NERC Field Spectroscopy Facility, NERC Geophysical Equipment Facility and the rest of Team Shrub. I will also give a shout out to a new Team Shrub member Karol Stanski who is an informatics master’s student co-supervised by Chris Lucas working on automated processing of some of our drone data – counting flowers from above. Drone research definitely takes a whole team and as always we are indebted to you guys on the outside for helping us keep the drones in the air and the sensors working to keep the data flowing in.

In the ShrubTundra Project, we are using the drones to understand the following four scientific questions:

- How does landscape-level phenology (the timing of green up, flowering and browning and browning of tundra plants each year) relate to on-the-ground and satellite observations?

- What environmental factors (such as soil moisture) explain where the greenest parts of the landscape are found and where vegetation change is occurring most rapidly? And are there particular spatial scales of investigation where these relationships are strongest?

- How can we scale vegetation change observations from the individual plant, plant community, landscape to biome? And are the relationships between on-the-ground, drone and satellite data found at our focal research site on Qikiqtaruk-Herschel Island consistent with data from other sites around the Arctic?

- What are the rates and volumes of permafrost and coastal erosion disturbances across the landscape and are these rates accelerating?

In our final year of the project, funded by the UK Arctic Bursary programme, we are teaming up with Trevor Lantz from the University of Victoria and Robert Fraser from Natural Resources Canada working at other sites in the Western Canadian Arctic, and other researchers working at sites around the Arctic through the High-latitude Drone Ecology Network to try to test these questions in a coordinated way across the tundra biome.

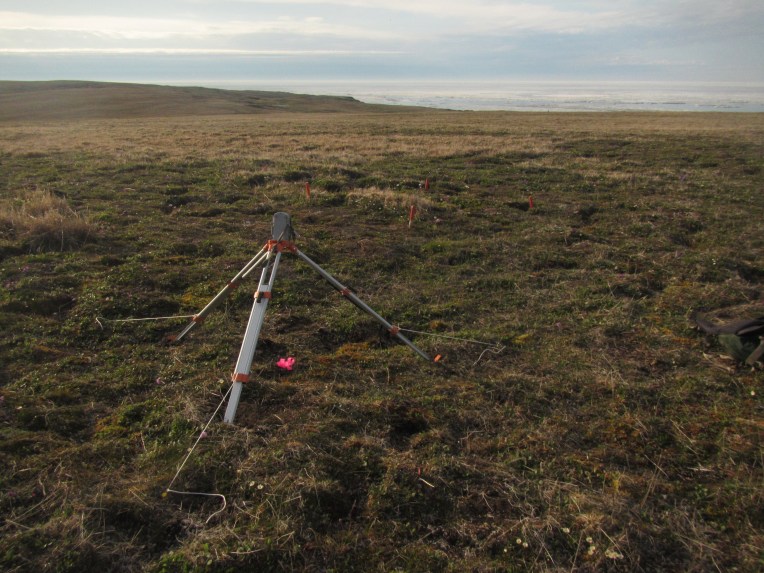

Collecting data using drones is a bit different from other ecological work. You are much more dependent on the weather. Too much wind, any rain, any fog, even just clouds can all get in the way of drone flights. There is nothing so frustrating as carrying all of our equipment out to the most remote of our sites only to find that the weather has changed and we can no longer fly. This summer we have been chased out of the field by thunderstorms, sudden wind gusts and downpours of rain. But recently the weather has been pretty good for drone flying and we have had some really big data collection days – with over 26,000 images and 70 GBs of data collected in six hours of airtime around solar noon, using quadcopters and fixed wings. When you collect that much data in one day there is a lot of post data collection work to do that we have been calling “metadata”, but that really only describes part of the work from charging drone batteries to collating images, reviewing their quality and writing up all of the flight information.

The thing with working with drones is sometimes you run across “drone troubles”. Whether it is too few satellites, compass calibration issues, funky cable connections to the camera sensors, there are always different types of challenges to the work. One thing we have learned from doing drone work in the Arctic is to bring spares and to plan for every contingency. This summer we have expanded our drone fleet: at one point, we figured there were around 15 drones or potential drones on the island, including spare parts. We have brought with us two hexacopters (Tarot 680s), five fixed-wing drones with most of the spare parts for around three more (Zeta FX-61s), three DJI Phantoms (two DJI P4 Pros and one P4 Advanced), two 3DR Iris+ and, for the first bit of the season we also had a Parrot Disco Ag and a DJI Mavic. All of these different drone platforms provide us with many options for data collection, from fine-scale data collection flown at 20 m height for structure-from-motion work to make 3D models of shrub canopies to ‘high altitude’ 120 m flights for large extent models of tundra greenness across the landscape.

So, what have we found so far with our drone work? Most of the data processing is still ahead of us, but there have been some data presents so far this season. We have observed over 10 m of coastal erosion in a two-week period at the edge of the floodplain near our camp – that is very fast even for this rapidly eroding island. We have also observed rapid rates of thaw in the permafrost disturbances known as retrogressive thaw slumps, with large sections of the ground being lost to the mud cesspool below over the past year. Our on-the-ground phenology data indicates that this is an early year, and we are hoping that the drone data also shows that pattern in the time series of multispectral imagery.

For future updates on all things drone, stay tuned to the blog over the field season and through the fall. And if you are keen on high latitude drone ecology yourself, then sign up for the HiLDEN network!

By Isla