Tundra resilience over space and time

Are tundra ecosystems getting closer to a tipping point?

Interested in the project? We are offering a postdoc position.

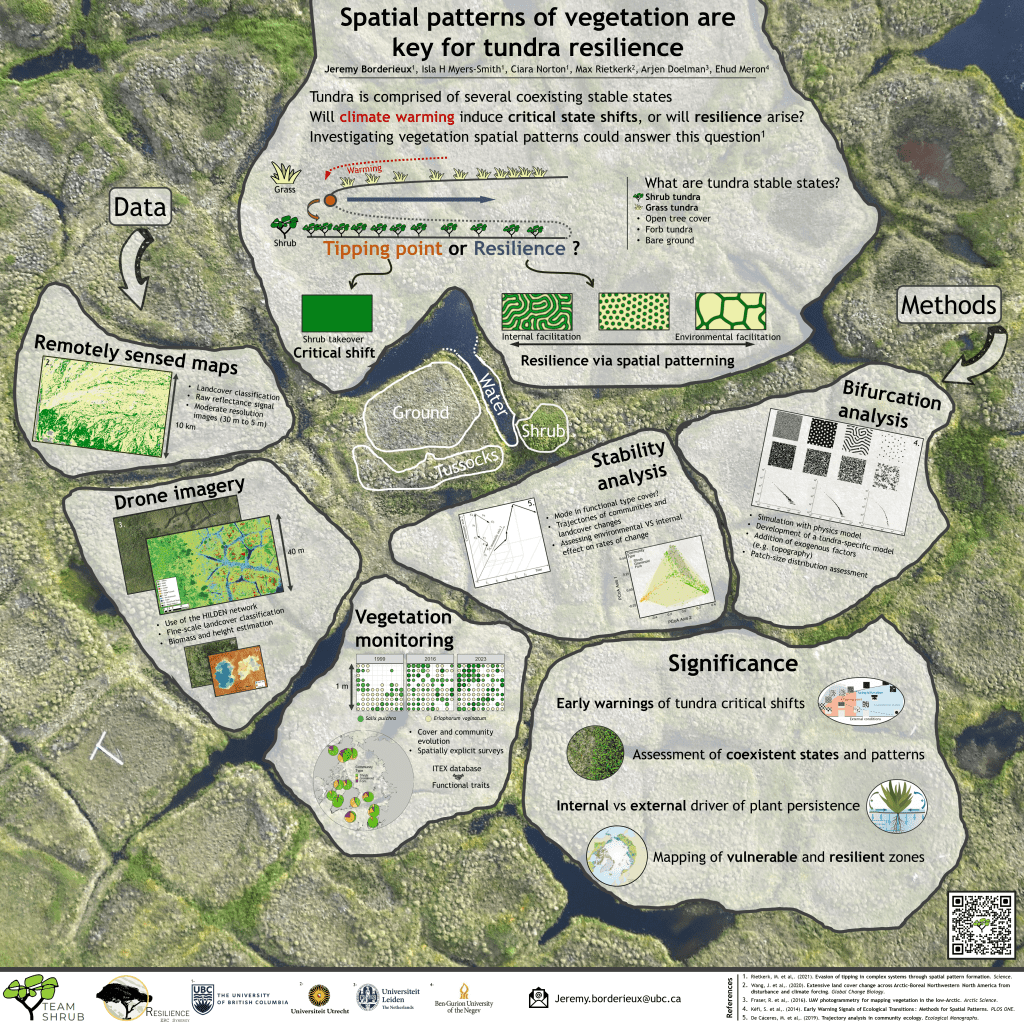

The Resilience project, funded by an ERC synergy grant (2023 to 2029), will investigate how tundra, savanna and dryland ecosystems respond to climate change focusing on shifts tundra vegetation and permafrost thaw. In particular, the Resilience project asks how spatial patterns of vegetation and disturbances might influence how ecosystems either undergo or withstand change. The Resilience Project is an interdisciplinary collaboration between mathematicians and physicists and ecologists from Leiden University, Utrecht University, Ben-Gurion University and the University of British Columbia to advance our fundamental understanding how ecosystems are responding as the planet warms.

Ecosystems can respond in more subtle and more dramatic ways to global change, with some changes being irreversible processes on human time scales. For instance, an expansion of shrubs is often a result of clonal growth with shrub canopies shading out surrounding plants growing beneath them. Shrub seedlings establish best where there is bare ground. This can create a feedback between disturbances and new recruitment of shrubs, with more disturbances more shrubs can start growing in tundra ecosystems. Over decadal time scales disturbance can result in shrub establishment and encroachment that can alter tundra ecosystems.

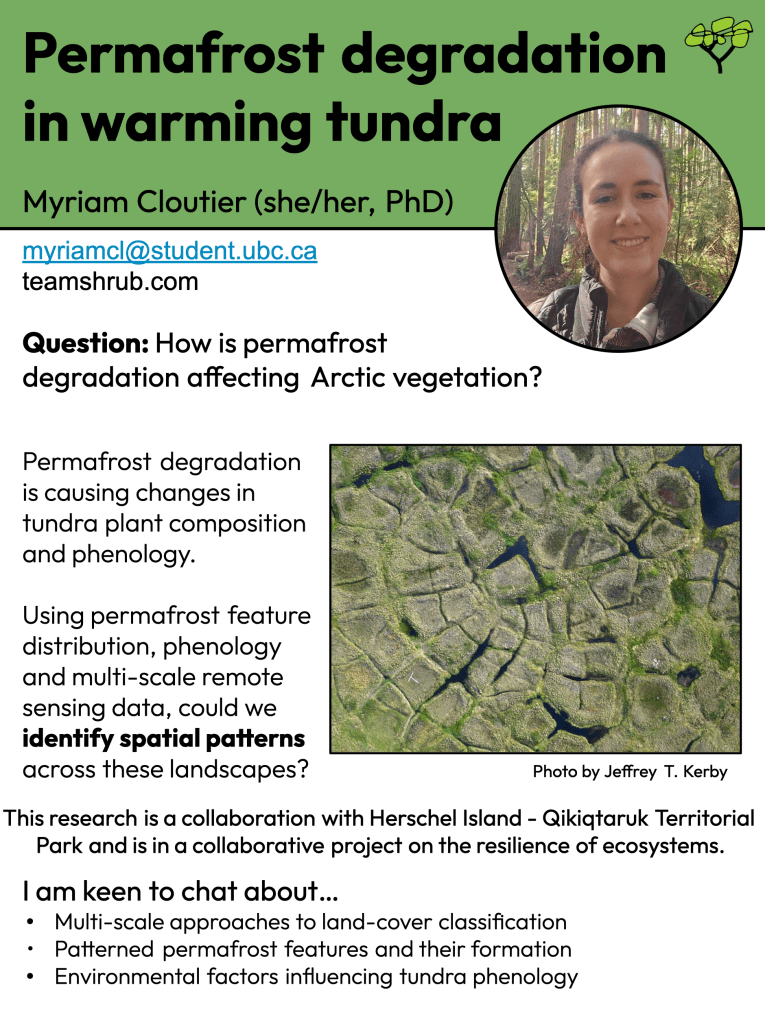

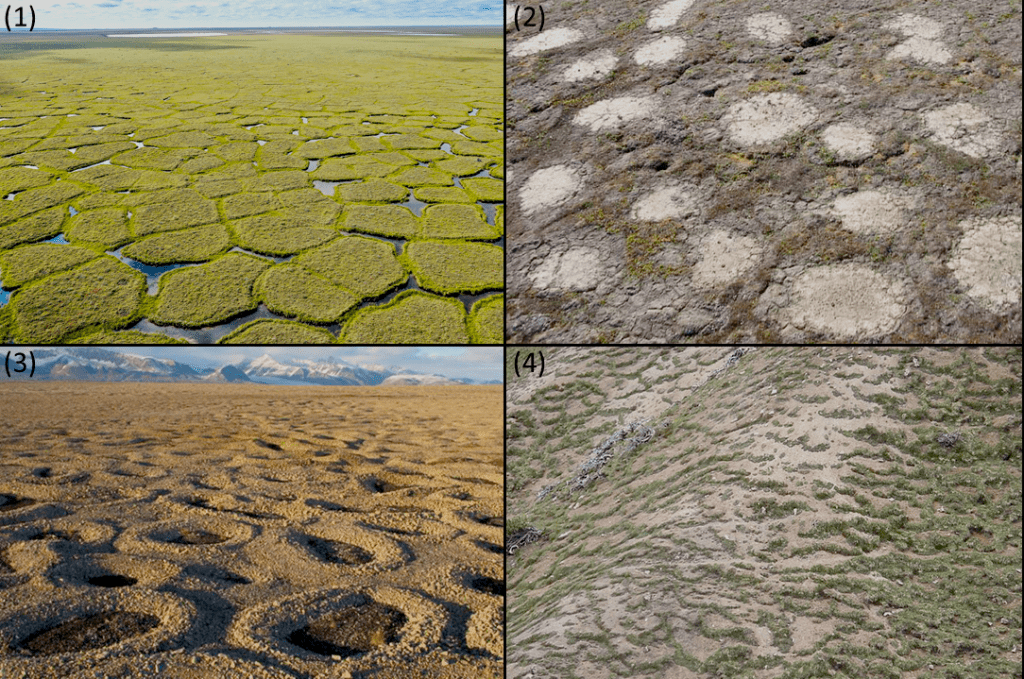

Spatial patterns are found across the tundra biome. Polygonal ground is formed by the thawing of ice wedges, ice that formed over millennia in cracks in the ground. As the ground cracked, water poured into those cracks, freezing and re-cracking and filling with water and freezing year after year, slowly expanding over time to form deep and wide chunks of ice that look like giant teeth in cross-section.

Frost boils are formed when winter freezing and summer thawing year after year push rocks and soil to the surface that “boil” over onto the surrounding tundra. Sorted circles form in a similar way with freeze-thaw action bringing larger rocks to the surface in circular patterns that look like the rocky version of mushroom fairy rings.

Along slopes, stripes of tundra can form through solifluction, the movement of frozen soils ever-so-slowly down slope. Solifluction lobes make the mountain slopes look like icing dripping off of a warm cake but in multi-decadal slow motion. Despite spatial patterning being prevalent around the Arctic, we don’t yet know what impact patterning might have on how tundra ecosystems are responding to climate change.

Early warnings and trajectories of dramatic shifts can be assessed with spatial data, looking at the spacing of plants and the structure of ecosystems and quantifying the size and rate of permafrost disturbances. We will explore questions:

- How many tundra ecosystems have distinct spatial patterns and what patterns can be found across the tundra biome?

- How to tundra plants arrange themselves within tundra communities and how do these patterns shift over time?

- Is climate warming leading to more or less spatial patterning in tundra ecosystems?

- Do spatial patterns make ecosystems more or less vulnerable to abrupt permafrost thaw such as landslides?

We will integrate understanding of spatial ecosystem processes from other vulnerable environments such as savannas, deserts and coral reefs to assess how spatial patterning within tundra ecosystems are similar or differ from other patterns found elsewhere across the planet. And we will ask whether spatial patterning within the tundra biome causes those systems to be more vulnerable or resilient to rapid climate warming.

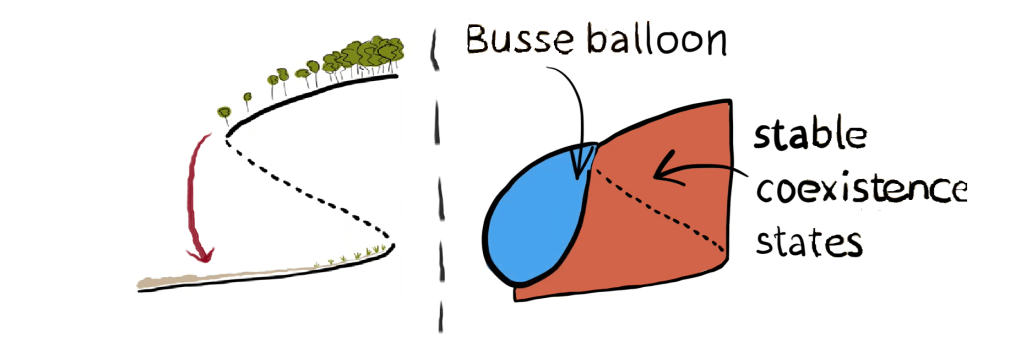

The Arctic is warming nearly four times the global rate causing profound environmental and vegetation changes. We don’t yet know if vegetation changes such as shrub expansion and increasing permafrost disturbances such as landslides (active layer detachments) and thaw slumps are close to a critical irreversible shift –– a tipping point. In savannas, this tipping point can be assessed by studying vegetation patterning in space which could provide critical insights into the future of tundra vegetation if this framework holds true in tundra ecosystems. New developments from this framework suggest that spatial pattern formation through facilitation or microtopography, could promote resilience of ecosystems to climate change. But is this the case in tundra ecosystems?

It is critical to assess whether tundra undergoes dramatic shifts as many ecosystem functions of the tundra depend on the cover of the main vegetation type. A shift from herbaceous to shrub species will affect the foraging, nesting and distribution of wildlife and poses implications on land management for northern communities. Increase in shrub vegetation will reduces the reflectance of the surface of the tundra. A darker tundra surface will absorb more of the sun’s heat, bringing more heat into the system and potentially accelerating climate change.

Shrubs have more biomass than other tundra plants, and thus trap carbon in tundra ecosystems, but the warmer soil temperatures, deeper thaw of the ground under shrub canopies and organic soils can lead to greater decomposition and potentially carbon losses from these ecosystems and possibly greater rates of permafrost disturbance and even tundra fires. Crossing a tipping point in permafrost disturbance will also release some of the carbon stored in tundra soils to the atmosphere and oceans, as well as threatening landscapes of cultural importance.

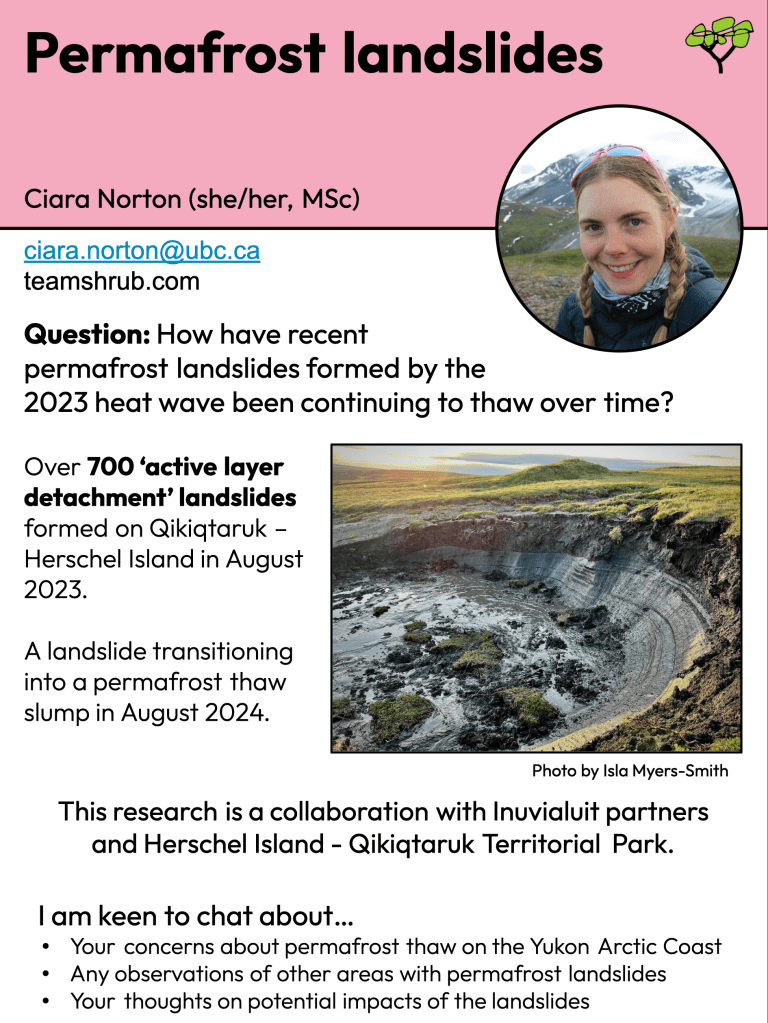

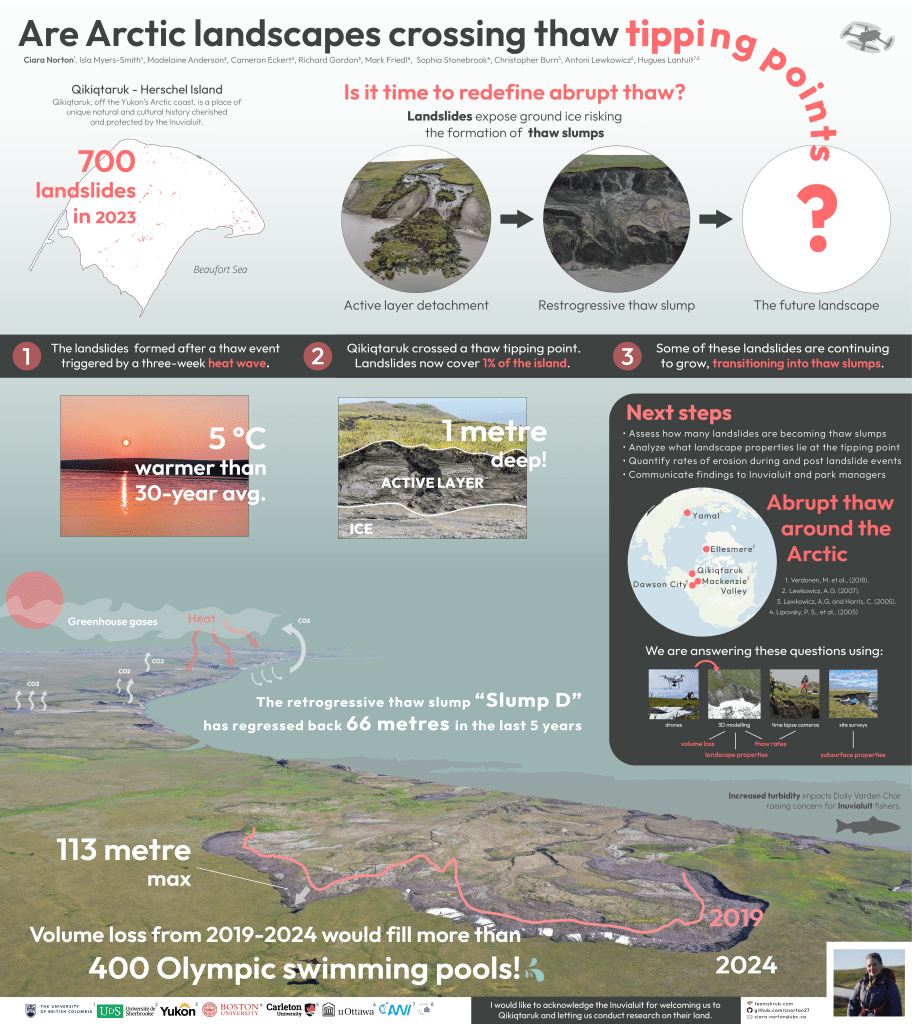

In 2023, one of our Resilience Project field sites, Qikiqtaruk – Herschel Island, experienced a heatwave that led to the formation of over 700 landslides across the island. This magnitude of rapid permafrost thaw and disturbance across this tundra landscape illustrates how vulnerable tundra landscapes are to climate warming, but questions remain. Why did landslides occur in some places and not others, did tundra vegetation such as shrub cover help to counter act the development of landslides?

The resilience project will use data from all spatial scales to study the spatial patterning of tundra response to climate change. Thanks to the International Tundra Experiment, we will study vegetation changes with sub-metre measurements of plant cover. We will complement this vegetation analysis with five-centimetre resolution drone imagery collected by our team and from the HILDEN network, allowing us to precisely map vegetation patterning and produce precise 3D models of permafrost slumps.

This combination of ecological and spatial data used with stability analysis will answer the question “under which conditions are tundra ecosystems are vulnerable or resilient to warming”. We will scale up our result with satellite imagery to quantify the amount of spatial patterning across the tundra biome and create predictions of more vulnerable or more resilient parts of the Arctic.

Studying spatial patterning of vegetation will increase our general understanding of how much shrub and grass coexistence stems from these plants facilitating each other versus environmental variation such as waterlogged soil and microtopography (see photo above). Alongside a better understanding of the increase in frequency of landslides, our results will allow us to refine our prediction of biome wide shifts in vegetation cover and landscape integrity. For instance, a better understanding of shrub expansion and the CO2 released in the ocean and atmosphere by landslides will improve our understanding of the vegetation-carbon-climate feedbacks that could accelerate climate change for the planet as a whole.

Words by Jeremy Borderieux

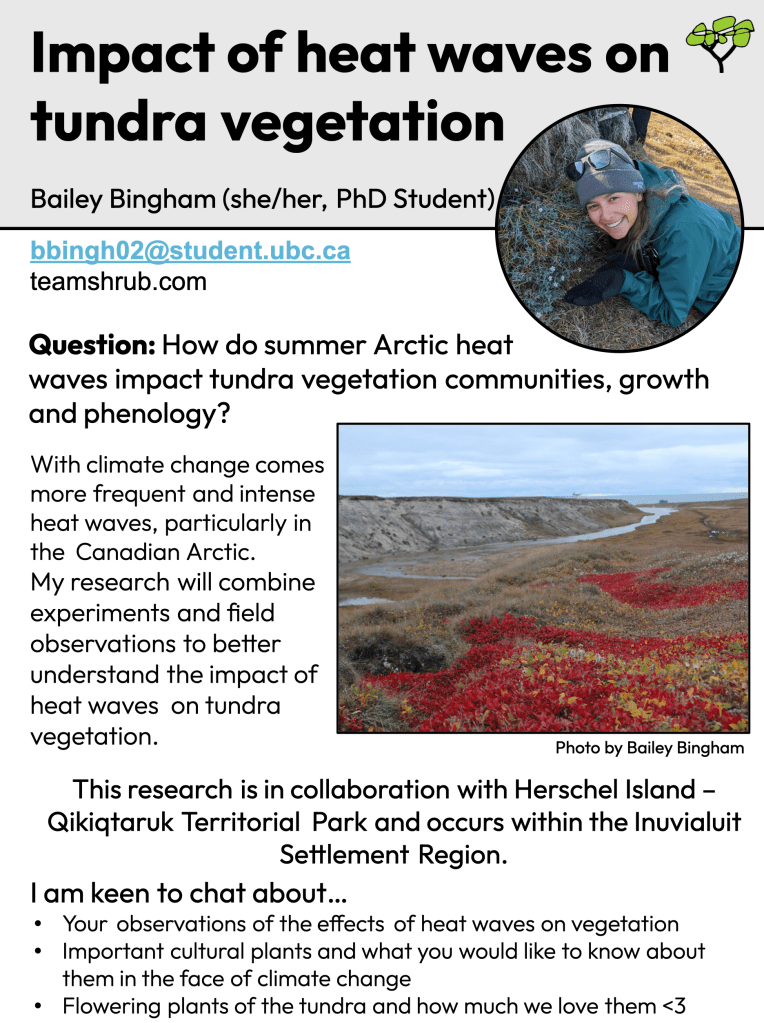

To find out more about this research, check out these ArcticNet posters by Jeremy Borderieux and Ciara Norton:

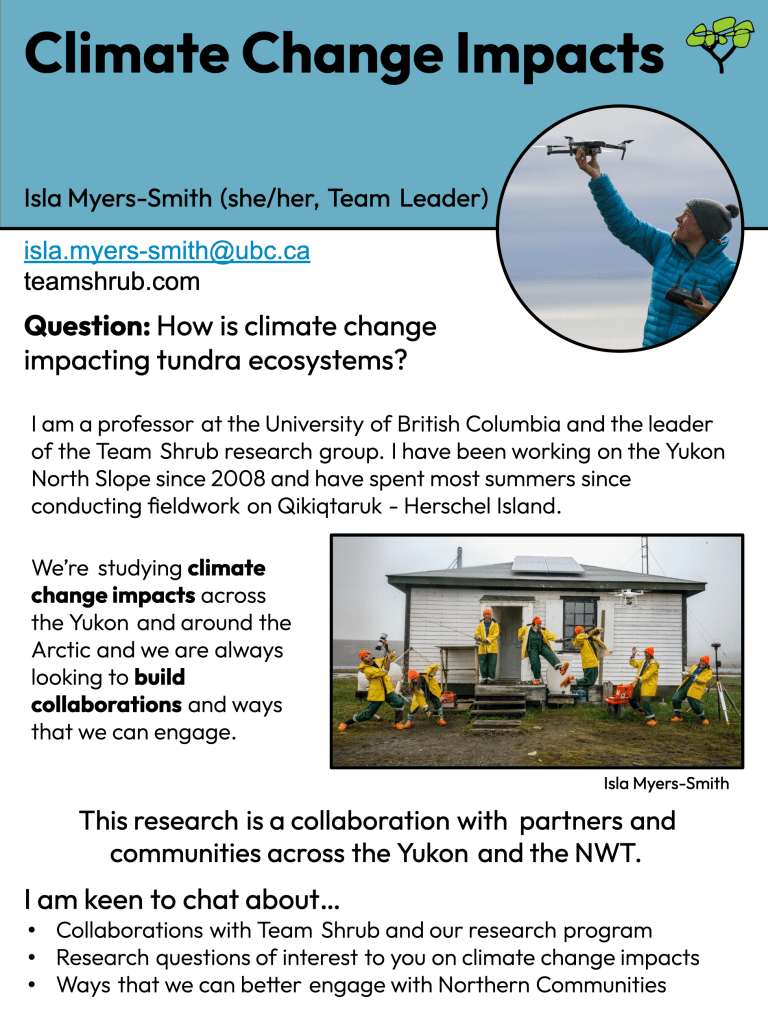

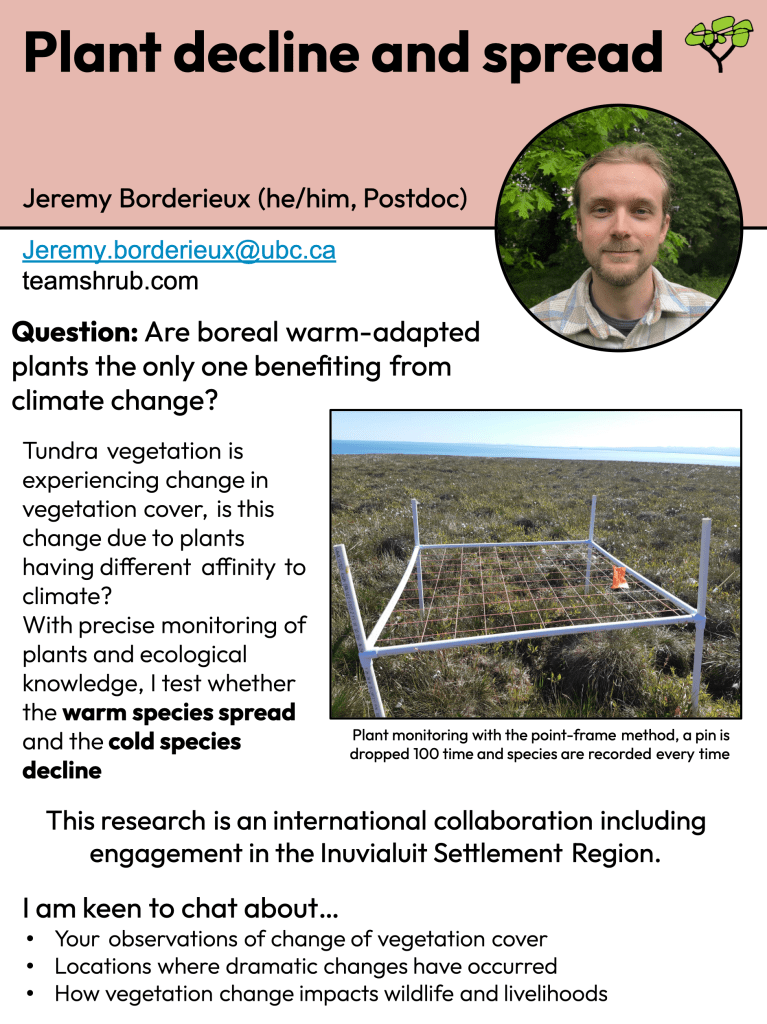

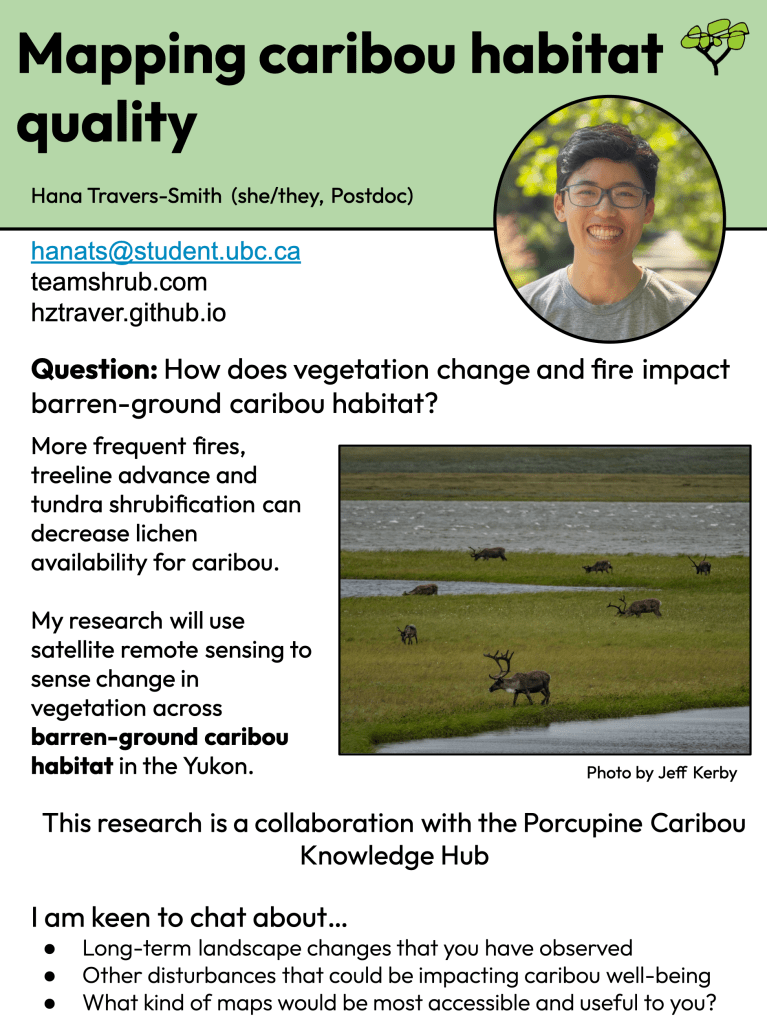

Meet the Team Behind the Research